by

Annie Waldman

, ProPublica, photography by

Cydni Elledge

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive

our biggest stories

as soon as they’re published.

Editor’s note:

ProPublica obtained parents’ consent to feature their children in this story.

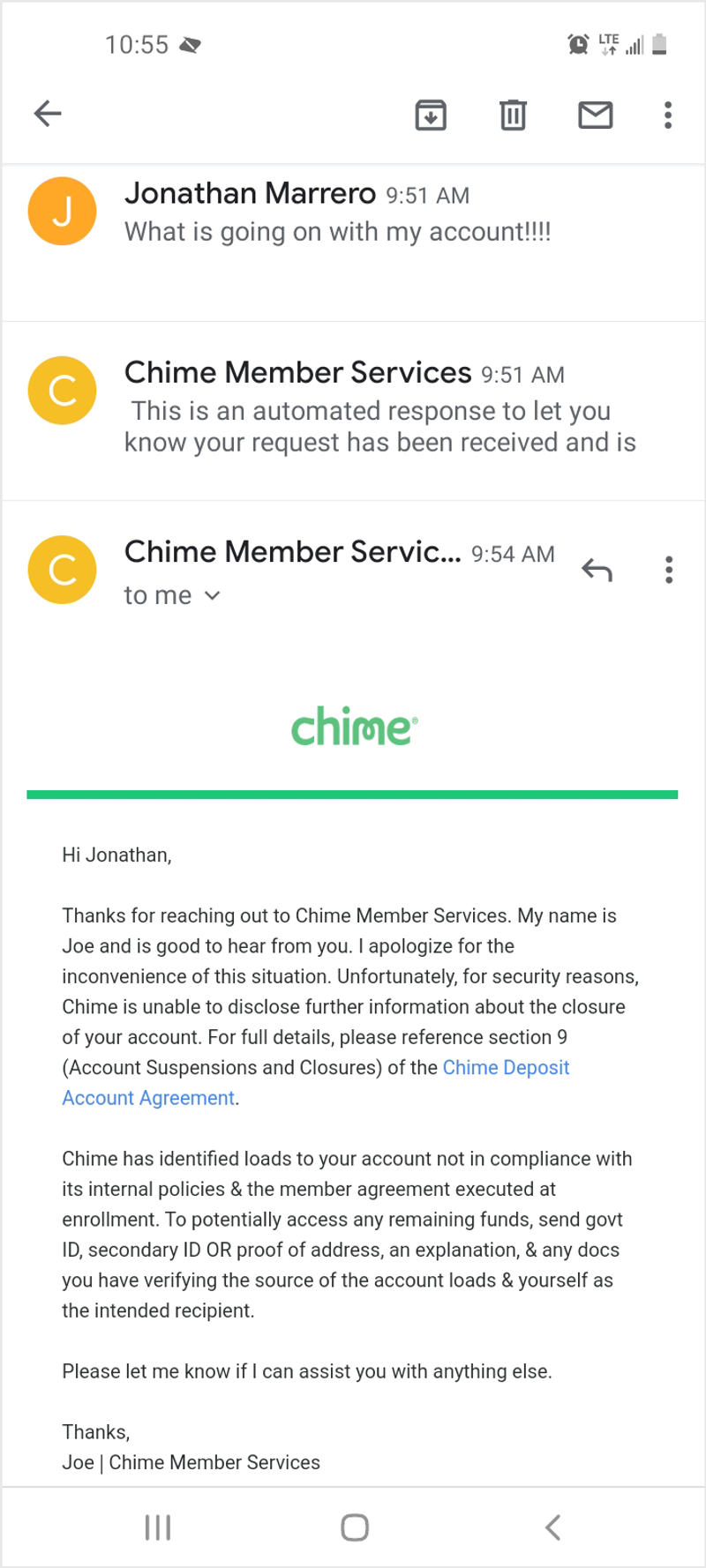

Ashlee Thompson turned on her camera.

At the other end of the screen one morning last September was a third grader she’d never taught. To assess his reading, Thompson showed the boy a string of letters.

S

B

C

He made a few guesses, but seemed to only recognize the ones in his first name.

Unsettled, Thompson shifted to words that most 8-year-old children can recognize, if only by sight. She enlarged the text and held her pointer on the screen.

Of

And

Me

Never miss the most important reporting from ProPublica’s newsroom. Subscribe to the Big Story newsletter.

The boy’s mother sat behind him, encouraging him to read. He grimaced and shook his head. He had never learned how, he told his mother. He had transferred in from a charter school, but like many of Thompson’s students who’d been in the district for years, he was arriving in her class as though he was starting kindergarten. As his mother began to cry, Thompson turned off her camera so they wouldn’t see her own eyes glaze over with tears.

Never miss the most important reporting from ProPublica’s newsroom. Subscribe to the Big Story newsletter.

At the start of the 2020 school year, teachers across the country entered their classrooms riddled with anxiety over how much their students could possibly learn amid a pandemic, between the glitch-prone experiments with remote learning and in-person classes that could be interrupted by a single positive coronavirus test.

Never miss the most important reporting from ProPublica’s newsroom. Subscribe to the Big Story newsletter.

Thompson, at 32, had a lot more hanging over her.

The Michigan legislature had chosen this year, of all years, to enforce a strict new literacy law: Any third grader who could not read proficiently by May could flunk and be held back.

Never miss the most important reporting from ProPublica’s newsroom. Subscribe to the Big Story newsletter.

For Benton Harbor, a small, majority-Black city halfway between Chicago and Detroit, the implications were immense. As Thompson screened her 35 students that fall, she realized 19 were not at grade level. She worried that holding them back could do more harm than good, and studies supported this fear; it could bruise their

confidence

, lead them to

act out

and even

decrease

their odds of graduating from high school.

Never miss the most important reporting from ProPublica’s newsroom. Subscribe to the Big Story newsletter.

As if Thompson did not have enough to worry about, there was this: The existence of her entire school district hung in the balance, and with it, the very fabric of her hometown.

For the last quarter century, schools in Benton Harbor had struggled to survive as students fled for charters and majority-white districts in neighboring towns. Because a district’s funding is tied to its number of students, Benton Harbor’s budget shrank. It cut academic offerings, froze teacher pay, closed school buildings and consolidated students into crowded classrooms. As its resources eroded, so did students’ performance on tests.

Michigan had found a remedy for such ailing districts: dissolving them. It had happened eight years ago to two other majority-Black cities, Inkster and Buena Vista. Students were absorbed into surrounding districts without a

guarantee

they would be attending better schools. Inkster residents, who feared losing their sense of identity, scrambled to start a

museum

so that their children would know they had once rallied at homecoming games around the Vikings football team.

This existential threat has loomed over Benton Harbor since 2011, when former Gov. Rick Snyder began to

consider

whether the state should install an emergency manager to run the city’s schools, a takeover Inkster once

faced

before it was ultimately dissolved. In January 2017, his administration listed several of Benton Harbor’s schools among the least proficient in the state and

slated

them for closure. The state offered the district a temporary reprieve if it entered into a partnership agreement that

mandated

that the schools improve. But in May 2019, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer announced a plan to

dissolve

Benton Harbor’s high school. To illustrate the dire state of education in the district, she

cited

the poor

test scores

of students in the third grade, a crucial year in which kids

traditionally

pivot from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.”

The library at Hull Elementary, Thompson’s school.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

The district ran six schools: one for preschool and kindergarten, one for first through third grade, one for fourth and fifth grade, a middle school, a high school and an alternative program. Thompson feared that if the high school was dissolved, it was only a matter of time before parents stopped enrolling younger students and the entire district evaporated. What parent would want to send a child down a path that dead-ended after the eighth grade?

Thompson, a wide-eyed learner who tackled problems with an analytical mind, sent community leaders a six-page letter, complete with a color-coded data table she assembled, arguing that transferring Benton Harbor’s students outside the city wouldn’t necessarily bring them success.

Proficiency is not contagious,

she wrote,

but comes from years of effective educational support, practice and preparation, which the lack thereof is why our students are behind.

Amid public outcry, the state backed down from threats to close the high school and began to work with the district to address its crisis. Part of the plan was new

leadership

, and in February 2020, the district brought on Andraé Townsel, an energetic superintendent who grew up in Detroit and had a singular mission to turn the schools around. A month later, though, the pandemic interrupted all plans, leaving the fate of the schools once again in question.

Thompson didn’t want to think about what would happen if most of her students were held back. Any failure, she worried, would be cast as theirs.

She was regarded by many Benton Harbor parents as a miracle teacher. She had attended school with some of them and lived in the community; she cared for their children like they were her own. They were not on equal footing with their peers for reasons outside of their control. It was on her to bridge the gap, one that would widen even further amid a pandemic.

“Even if I had magic,” she said, “I couldn’t do this.”

Thompson at home.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

When Thompson was a third grader in Benton Harbor, her brick schoolhouse glowed burnt orange in the afternoon, with classrooms bathed in light among trimmed, green lawns. The schools were the pride of the city, one of the poorest in Michigan, depressed for decades by discriminatory housing

policies

and deindustrialization; as manufacturing jobs began to vanish in the 1960s and ’70s, white families fled in droves.

Benton Harbor’s Black families won a critical court

ruling

in 1977, after white neighborhoods drew up plans to peel off from the city and join communities with fewer Black families. These were “transparent attempts” to dismantle Benton Harbor into “separate and unequal White and Black school districts,” concluded U.S. District Judge Noel Fox. The court mandated

integration

between Benton Harbor and its surrounding communities through a voluntary busing plan, allowing students to choose where to attend school. Anticipating the financial impact of an exodus, the court ordered the state to pay Benton Harbor for each child who lived within its boundaries,

regardless

of where they chose to attend school.

For decades, funding from the desegregation case buoyed Benton Harbor and brought national recognition to its schools. Creative Arts Academy and McCord Renaissance Center, two of the magnet programs set up under the order, were

named

Blue Ribbon schools by the U.S. Department of Education, one of its highest academic honors.

Thompson, who attended McCord, thrived in Benton Harbor’s schools. A self-professed bookworm, she spent hours in the library reading The Baby-Sitters Club and Goosebumps books and writing in her journal. Her teachers, many of whom lived in the community, pushed her to excel, and in high school, she volunteered as a library aide, learned Spanish, French, physics, psychology and creative writing, and took advanced placement courses. “I didn’t know that kids had to struggle to attain an education because I never witnessed that growing up,” she said.

Even so, it had become common for parents to consider sending their children to schools outside the district. She was in 10th grade when her mother decided she would be better served by transferring to a nearby town. “I hated it,” Thompson said. “The teachers were all white and they didn’t have an individual interest in me. Some of the teachers, I don’t even think they even cared to get to know my name.” After a few months, she begged her mother to let her return to Benton Harbor High School, where she graduated among the top 10 students in her class.

She and many others were unaware of a radical change that was underway. Michigan’s then-governor, Republican John Engler, had pushed to end the desegregation order, citing the cost and insisting the state had done everything it was supposed to do to ensure Benton Harbor’s success. Any shortcomings in student performance, the state

argued

, had nothing to do with intentional segregation. In 2002, a federal judge dismissed the case. The payments were phased out by 2006, Thompson’s final year of high school.

The following school year, the district faced a $3 million shortfall, roughly the amount of money it had received annually from the state under the desegregation order. To offset the loss, the district began to cut its academic offerings, which prompted students to leave for other schools. “It was a spiral effect,” said Sheletha Bobo, the district’s assistant superintendent for business and finance from 1999 to 2011. While critics and state officials have long attributed the district’s financial troubles to mismanagement or

accounting errors

, administrators contended that enrollment and funding losses played a central role. The fewer students Benton Harbor had, the less money it was allocated by a state formula that distributed school funding based largely on student

head count

. School finance experts have

argued

the math shortchanges districts that serve a higher percentage of low-income and at-risk students, who are more expensive to teach.

Recognizing that it needed to increase enrollment to climb out of its financial turmoil, the district brought in Michigan native Magic Johnson for an advertising campaign. “I’m Earvin ‘Magic’ Johnson,” he said in a 2010 radio spot. “[I’m] encouraging parents and students to find out why people are rediscovering Benton Harbor Area Schools. … Quality learning, every student, every day.” But even a basketball legend couldn’t bring students back. By 2011, the district’s annual budget

deficit

had

risen

to $16.4 million.

Weeds grow at Montessori Academy at Henry C. Morton, an elementary school closed after enrollment in Benton Harbor plunged.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

To keep its bills paid, Benton Harbor took on more than $10 million in emergency loans from the state. The weight of the debt led to even more cuts in the district, which hemorrhaged students and money. Enrollment plunged from 3,500 students in 2010 to fewer than 1,800 in 2020. More than two-thirds of the city’s children attend schools outside the district, amounting to a staggering

loss

of $24 million in funding each year.

The magnet programs, including Thompson’s former school, were shuttered. The cosmetology and health care tracks were cut. The high school no longer offered calculus or advanced placement courses. In 2019, for a student body of nearly 600, only one instructor was certified to teach mathematics. And that year, about

half

of the district’s teachers were long-term substitutes, many lacking the credentials or experience to manage classrooms sometimes crammed with 30 students or more.

Test scores declined. During the 2007-2008 school year, 64% of Benton Harbor’s third graders were

deemed

proficient readers, compared with 81% across Michigan. During the 2018-2019 school year, according to a different test the state had switched to using, less than 6% could read

proficiently

, compared with 45% across the state.

And the buildings, all constructed before 1961, bore signs of disrepair. The school where all of the district’s third graders learned, International Academy at Hull, was plagued by toxic mold. A musty smell often wafted through the hallways, and mildew rings stained ceiling tiles. For years, teachers had noted the building’s crumbling state, filing maintenance orders that were rarely filled. They trapped mice in the classrooms, and on stormy days, they caught rainwater in buckets, carefully positioned between children’s desks.

A dozen other school buildings sat abandoned, haunting the city like ghosts. Their windows were boarded up and their playground equipment was corroded. In one building, parts of the ceiling were strewn across the floor.

Fair Plain Northeast Elementary School, closed.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

Thompson had never planned to be a teacher. After high school, she enrolled in Wayne State University but dropped out after her first year, given the high cost and her uncertainty about which career direction to take. She found work in a hotel and later cared for elderly patients in a residential home as a certified nursing assistant. But after the birth of her first three children, she decided to try college again. She had a natural talent for extracting lessons from ordinary moments, showing her kids how caterpillars metamorphose into butterflies and sliding magnets near metallic pipes to explain polarity. She enrolled at Western Michigan University to pursue an education degree.

For an assignment, she compared the learning outcomes of Benton Harbor’s students to those in St. Joseph, a wealthy town across the district border, where less than a third of the schoolchildren qualified for free lunch and three-quarters of its students were white. Over decades, the waterway between the towns, the St. Joseph River, has come to mark one of the most

segregated

school boundaries in America. In St. Joseph, more than 63% of third graders could read proficiently, compared with less than 6% in Benton Harbor, where more than 90% of students are Black and live in low-income households.

The starkness of the inequality stunned her, but it echoed the persistent national reality that students of color were

demonstrating a lower proficiency

in reading and math than their white counterparts, with similar gaps between students living in poverty and those who were not.

And while Benton Harbor’s schools are in high-poverty areas, and thus receive more federal funding and have higher general revenue than St. Joseph, Benton Harbor

spent

$1,000 less per student on basic instructional programs in 2019, in part because of its high debt

load

, on which the state was collecting with about 2% interest. That year, the district was $16 million in debt and

spending

$700 per student on annual repayments, according to the state.

Even though teachers across the river made $17,000 more, on average, Thompson started in Benton Harbor’s schools in 2018 and took over a third grade class midway through the school year. “Our students needed somebody that could help, somebody that could believe in them,” she said. In May 2019, she was certified to teach. But the following spring, just as her students were making the leap from robotically reciting words to fluent reading, the coronavirus ground the school year to a halt.

Schoolbooks at the closed Montessori Academy at Henry C. Morton.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

While the pandemic caught everyone off guard, disadvantaged districts were less ready to adapt to school shutdowns. Most of the students in St. Joseph had access to computers at home, in part thanks to an

initiative

supported

by the district’s philanthropic

foundation

. Within about a month, 97% of elementary students were

learning

online. In Benton Harbor, however, more than 40% of homes

lacked

broadband internet access and 25% did not have a computer. Thompson and her colleagues huddled around copy machines printing out assignments and spent days tracking down families and checking on their welfare. They finished distributing laptops and tablets, the majority of which were

more

than six years old, by the end of the summer.

This divide was playing out across the country, as captured in a national teacher survey that

spring

. Teachers in majority-Black schools said 34% of the students didn’t have the necessary technology to engage in remote learning, compared with 19% of kids in schools with few Black students. The gap was even wider between poor and wealthy schools.

The pandemic also brought new urgency to the country’s quiet

crisis

of dilapidated school facilities. Benton Harbor administrators had more to worry about than the average district when it came to planning for in-person instruction in the fall. In addition to wrestling with social distancing requirements, they had to figure out how to safely teach kids at Hull Elementary, where, in the spring, specialists had found levels of mold so toxic that they recommended shutting down the building. The new location— a shuttered school they were cleaning out — was not yet ready, so administrators relied on portable classrooms and white wedding tents, along with a plastic tarp they put up to cordon off the remediated classrooms from the toxic wing of the school.

Not many parents knew about the mold, but a majority still insisted on a virtual option when the district surveyed them on their preferred mode of instruction for the fall. The coronavirus had

surged

through the county’s nursing homes and rehabilitation facilities, and reports from

Detroit

on the disproportionate number of

deaths

among African Americans had trickled into Benton Harbor, prompting many to stay home out of fear. Nationally, Black students were

disproportionately more likely

to have lost a parent to COVID-19 and substantially

less likely

to have enrolled in in-person school, even as late as April 2021.

Roberta Taylor wished her two third graders could learn in a classroom that year; for them, every minute of personalized instruction made a difference. Her son, Calvin, had been held back once already, in the first grade. She feared the same would happen to her daughter, Na’Kiyrah, who had finished the previous school year behind grade level. But Taylor had congestive heart failure so severe that she’d had to quit her strenuous job as a certified nursing assistant two years earlier and live on disability payments. “If I caught COVID, I might not make it out,” she said.

Calvin, left, and Na’Kiyrah, Roberta Taylor’s son and daughter, at home.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

Tina Lash also chose virtual school. One of her three sons was asthmatic and had landed in intensive care a few years earlier. She knew a digital classroom was not an ideal learning environment for her youngest boy, Michael, whose brain ping-ponged from thought to thought. And her shifts at the local Bob Evans restaurant, where she was a manager, frequently overlapped with class hours. Her mother stopped working at Family Dollar and planned to sit with Michael to make sure he wouldn’t wander off.

Thompson, too, learned she had no choice but to teach virtually. That summer, her breathing grew labored and her chest throbbed so much she couldn’t eat. She rushed to the emergency room, where tests revealed that her own congestive heart failure, a condition she’d had for nearly a decade, had flared up. During her nine-day hospital stay, she asked her doctor whether it would be safe for her to teach in person. He adamantly counseled against it.

The month before school started, she converted her daughters’ bedroom into a third grade classroom. A shiny, plastic banner of letters lined the walls. A world map made of vibrant blue fabric dangled in front of the window. Stacks of books surrounded her, filled with tales of inspiring young protagonists: Leo the Late Bloomer. Zoey and Sassafras. Harry Potter.

Hull Elementary had assigned only Thompson to handle all virtual third graders. She tried not to panic when she got the roster; it listed 48 names. Over the last days of summer break, she split her class into two waves of students and, like a telemarketer, called dozens of parents, walking them through how to log in.

She was ready, or so she thought.

Thompson converted her daughters’ bedroom into a teaching space.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

“The sound is

eh

eh

eh

, E as in elephant, E as in echo, E as in red,” Thompson said on a Wednesday morning in early March, her eyes scanning her classroom grid of 15 fidgety third graders. “I want everybody to say the sound, and if you have low background noise, you can unmute.”

Na’Kiyrah, a bubbly 8-year-old, always eager to speak even without knowing all the answers, bobbed around next to her brother Calvin. She unmuted her computer and their distorted voices echoed through the class, filling the virtual room with a static buzz.

“Na’Kiyrah, I’m going to put you on mute because it seems like you have a lot going on,” said Thompson. “You guys, if you have a place that you have absolute quiet, please go to that place.”

It had gone like this for months. Thompson’s students often forgot to mute themselves, talking over each other. Sometimes the internet wavered and they unexpectedly vanished. Sometimes their connection was so weak that their camera could not turn on, leaving Thompson to wonder if a child was actually at the other end. At times, only a handful would log in at all.

Thompson had gotten off to a rough start when, after the first day of school, 53 kids showed up on her classroom roster; by the second week, it had ballooned to 79 kids. It turned out that some parents hadn’t answered the district survey about how they wanted their children to learn.

At the same time, she was supervising the virtual education of three of her own children, including her son who was in her third grade class. One day, when she couldn’t help her 7-year-old daughter with a computer problem because she was in the middle of a lesson, her daughter grew so frustrated that she broke down in tears.

How will I get through this?

Thompson had wondered, doubting not only her choice to teach virtually, but also her decision to teach at all.

A map of the world hangs over Thompson’s home classroom window.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

After the first two weeks and Thompson’s plea to human resources for help, her principal brought in another teacher, cutting Thompson’s class size down to about 35 children; she split them into two sections, each meeting for three hours a day, four times a week. In a normal school year, they would have had at least double that time to learn.

Thompson tried to make the best of the time she had. Even when she contracted COVID-19 in March, her head pounding and body weak, she worked through most of her illness, aware that for the three days she took off, her students would have to work on assignments on their own.

During her lesson on the short sound of the letter E, she switched her screen to a slide with the name Ben printed in thick black and red letters.

Her students repeated the word in an unruly refrain. Michael, an effusive 8-year-old who often provided his classmates with updates on his morning, was the last to respond.

“Sorry,” he announced. “I was talking to my mom.”

Diagnosed with attention deficits, Michael had been suspended so frequently in second grade that he was more than a year behind on his reading. That year, his mother had tried in vain to procure a special education plan for him.

For months, Thompson worked with him one-on-one and in small groups, cultivating a close bond. He reveled in multiplication drills and superhero tales, and for his own superpower, wished he could save those who died of COVID-19.

“I want freeze breath, heat breath and healing, so I could have healed my uncle,” he said. “I wish I could heal everyone that had the virus.”

Michael in his bedroom.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

By late winter, Thompson marveled at his growth: He was paying more attention and participating frequently, and his reading was slowly improving. But she worried that wouldn’t be enough progress for him or many of her other students, especially with the retention law looming.

Passed in 2016 through the state’s Republican-controlled legislature and signed by then-Gov. Snyder, the retention law, which required third graders to be held back if they were more than a year behind in reading by May, was supposed to go into effect in 2020, but it was suspended that year due to the pandemic. Both Republicans and Democrats introduced legislation to suspend retention again in 2021, but Republicans have

attempted

to make the law even more aggressive by mandating that both third and fourth graders would face being held back next year. The bill has yet to be voted on by the state Senate and House.

State Sen. Ken Horn, a Republican who sponsored the latest retention requirement, said it is intended to serve as a consequence for parents who might not pay attention to their children’s academic progress without it. “They don’t want their kids to have to go through this, their teachers don’t want to have their kids to go through this, then they will double down, and they will go to work,” he said. “If there are no consequences, then parents will go on doing what they’re doing.”

Thompson has heard the argument. “Personally, I’m sick of hearing that,” she said. “That’s somebody that doesn’t understand the economic disparities … doesn’t understand poverty.” Her own mother worked nearly nonstop to support her and relied on the school system, including trained teachers, to help her achieve success. “If our communities could do this ourselves, we wouldn’t be in this situation.”

Contrary to Horn’s assessment, Michael’s mother, Lash, had long been involved in her children’s schooling. She also had faith in Benton Harbor’s schools, which she had graduated from about 20 years before. She still FaceTimed with her favorite teachers, who had become her mentors, and believed that with the right resources, the district would turn around. But she felt that the abbreviated school days of the past year had shortchanged her son.

After work, in the evenings, she would read with Michael before he fell asleep, and she noticed that even in late winter, his reading was stunted. He would labor over each word, and often skipped the ones he didn’t know. Her older sons had never struggled like this.

While Lash and her son were constructing his new loft bed, she sat him down and told him she had decided she wanted him to repeat the third grade. “It’s not because you’re not doing good,” she said softly. “I want you to have a fresh start ... and be able to do the work.”

Michael was calm. “That’s OK, momma, whatever you think is better,” he said, and then changed the conversation to what color he could paint the walls of his room.

Parents whose children were learning virtually could opt out of testing and therefore the retention requirement. But Taylor wanted an honest assessment of how Na’Kiyrah and Calvin were doing. They had languished in the second grade. Her son accrued at least 10 suspensions, tied to behavioral problems that she believed originated when he was moved too quickly from special education to a mainstream track. Her daughter felt lost in the large class.

Taylor’s trust of Thompson ran deep — they had attended high school together and Taylor believed Thompson was her children’s best teacher yet. But this past year, her children’s attention had lagged. She tried to help them, purchasing multiplication flashcards and books and challenging them to spelling bees in the afternoons. But Taylor, who was back in college taking online courses to become a parole officer, knew she wasn’t a teacher.

Taylor does Na’Kiyrah’s hair in their living room.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

In early May, before the state’s test, Taylor bought new backpacks for Na’Kiyrah and Calvin, one decorated with dinosaurs and the other with sharks. Though she could barely afford her $97 utility bill that month, she hoped the new bags would boost their academic confidence.

The morning of the exam, just before her children hopped out of her weathered Ford Expedition, she stopped them. “Make sure you take your time and understand what you read before you answer any questions,” she said.

Na’Kiyrah nodded nonchalantly, which worried Taylor.

Na’Kiyrah, age 8.

(Cydni Elledge, special to ProPublica)

On a sticky afternoon in late May, while Taylor and her four children were watching “Trolls,” she heard the mail truck drive by. Her son brought two letters inside and put them at his mother’s feet on the couch. One, from the state, was addressed to the parent of Na’Kiyrah.

Taylor tore it open and began to read.

We understand that this may be difficult news to hear,

it said.

The more she read, the more she became consumed with how unfair it all felt, to raise the stakes for kids like this in the middle of a pandemic, when so many families like her own were stuck.

Taylor flicked off the movie and pulled Na’Kiyrah and Calvin to the dining table.

“You know what this is?” she asked Na’Kiyrah, holding up the note.

“No, what is it?”

“It’s the letter from the state saying that you are going to be held back.”

Na’Kiyrah’s eyes scrunched up in confusion. “For what?” she asked.

“I was telling you all school year long to be serious about this test,” Taylor said. “That was nothing to play with, it literally determines whether or not you go to the fourth grade.”

Her children went silent. Na’Kiyrah, with panic beginning to form in her eyes, studied her mother’s face.

“Mommy, are you mad at me?”

Taylor shook her head, relaxing her face. She wasn’t mad at her daughter. Taylor was frustrated with herself, wishing she could have done more for her children this year, despite her health limitations. She was relieved to learn that Calvin was promoted to the fourth grade, but knew that he passed “by the skin of his teeth” and feared that, if the Republican bill went through, he could face the threat of retention next school year too.

Of the 23 students in Thompson’s virtual class who took the test, five were flagged for retention. Such letters were sent to parents of 3,642 students statewide, accounting for about 5% of Michigan students who took the exam. (The state would not provide a racial or economic breakdown of those students, and neither the state nor Benton Harbor would disclose the number of third graders in the district who stand to be held back.)

“I look at the students like Na’Kiyrah and the other ones that just didn’t make it, and it breaks my heart,” said Thompson.

Despite its obstacles, Thompson views the year as a success. She witnessed growth in nearly all of her students, even though the state’s exams only measure how they compare to children across the state, many of whom have better resources.

In recent weeks, Whitmer reiterated her

opposition

to the strict reading law, as well as to the proposal to expand it. “Governor Whitmer has and will continue to oppose the state law that mandates retention based on reading scores,” said her spokesperson, Bobby Leddy, adding that with the pandemic, “it’s unfair to students, teachers, and parents to prevent children from taking the next steps in their education.”

Nationwide, students of color suffered a “strikingly negative impact” on their academic growth amid the crisis, with the gap continuing to grow markedly through last winter for Black and Latinx students. Those findings and others cited in this story were captured in a federal civil rights

report

commissioned by President Joe Biden on the impact of COVID-19 on America’s students. “The disparities in students’ experiences are stark,” the report concluded, calling the pandemic’s effects on existing racial and ethnic inequities “harsh and predictable.” “Those who went into the pandemic with the fewest opportunities are at risk of leaving with even less.”

Instead of giving Benton Harbor a break in the midst of the pandemic, state officials collected $420,000 in loan payments, with interest, from May 1, 2020, through May 1, 2021, according to the state treasury department. The department said it did not receive requests for loan assistance from the district during the pandemic. About $10 million of the debt remains.

Meanwhile, state legislators spent months sitting on $841 million in federal COVID-19-relief funds in an attempt to pressure the governor to

relinquish

her emergency powers to cancel sporting events and close schools when a community’s virus transmission rate went up. While some reports have suggested that Benton Harbor could

receive

more than $40 million in pandemic relief funds from the state and federal governments, according to district Chief Financial Officer Scott Johnson, the district had only

received

about $3.5 million as of June 22, money officials

could

use to enhance summer and online programming, prepare schools for the fall, upgrade ventilation in school buildings and address environmental issues like mold.

Whether the district will be able to pull itself out of not only the pandemic turmoil, but also the entrenched inequities of its past, only time will tell. “I want to earn our families back,” said Townsel, the superintendent, who has spent the year trying to recruit students to the district and helped secure a $3 million state grant to create new literacy programs over the next five years, which he believes

could

be a game changer. Whitmer has also

proposed

changing the state’s funding formula to provide more aid to districts with low-income or at-risk students.

But residents haven’t stopped worrying about what will happen if the turnaround plan fails and the state once again tries to dissolve its schools, like they did with Inkster and Buena Vista.

“They destroyed them — strong, rich-in-history Black districts that went through the same things that we went through,” said Reinaldo Tripplett, a district alumnus and former high school principal who sits on the school board and drives with a Benton Harbor Tigers mascot in his car. “Where we are today did not just happen overnight. Where we are today, in my opinion, had been planned a long time ago.”

Working with Thompson and Na’Kiyrah’s elementary school principal, Taylor was able to find a temporary reprieve for her daughter: Na’Kiyrah will enroll in summer school, which has been extended to eight weeks this year and started in late June.

At the end of the program, Na’Kiyrah will be reassessed, and if she passes, she will be able to move to the fourth grade with her brother. If she doesn’t, she’ll be forced to repeat third grade.

“I’m going to fourth grade,” Na’Kiyrah said, promising herself that she would pass at the end of summer. “This time, I’m going to know the answers.”

Are You Going to School During the Pandemic? Or Working There?

The library at Hull Elementary, Thompson’s school.

The library at Hull Elementary, Thompson’s school.

Thompson at home.

Thompson at home.

Weeds grow at Montessori Academy at Henry C. Morton, an elementary school closed after enrollment in Benton Harbor plunged.

Weeds grow at Montessori Academy at Henry C. Morton, an elementary school closed after enrollment in Benton Harbor plunged.

Fair Plain Northeast Elementary School, closed.

Fair Plain Northeast Elementary School, closed.

Schoolbooks at the closed Montessori Academy at Henry C. Morton.

Schoolbooks at the closed Montessori Academy at Henry C. Morton.

Calvin, left, and Na’Kiyrah, Roberta Taylor’s son and daughter, at home.

Calvin, left, and Na’Kiyrah, Roberta Taylor’s son and daughter, at home.

Thompson converted her daughters’ bedroom into a teaching space.

Thompson converted her daughters’ bedroom into a teaching space.

A map of the world hangs over Thompson’s home classroom window.

A map of the world hangs over Thompson’s home classroom window.

Michael in his bedroom.

Michael in his bedroom.

Taylor does Na’Kiyrah’s hair in their living room.

Taylor does Na’Kiyrah’s hair in their living room.

Na’Kiyrah, age 8.

Na’Kiyrah, age 8.