-

chevron_right

chevron_right

High-speed imaging and AI help us understand how insect wings work

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Yesterday - 20:16 · 1 minute

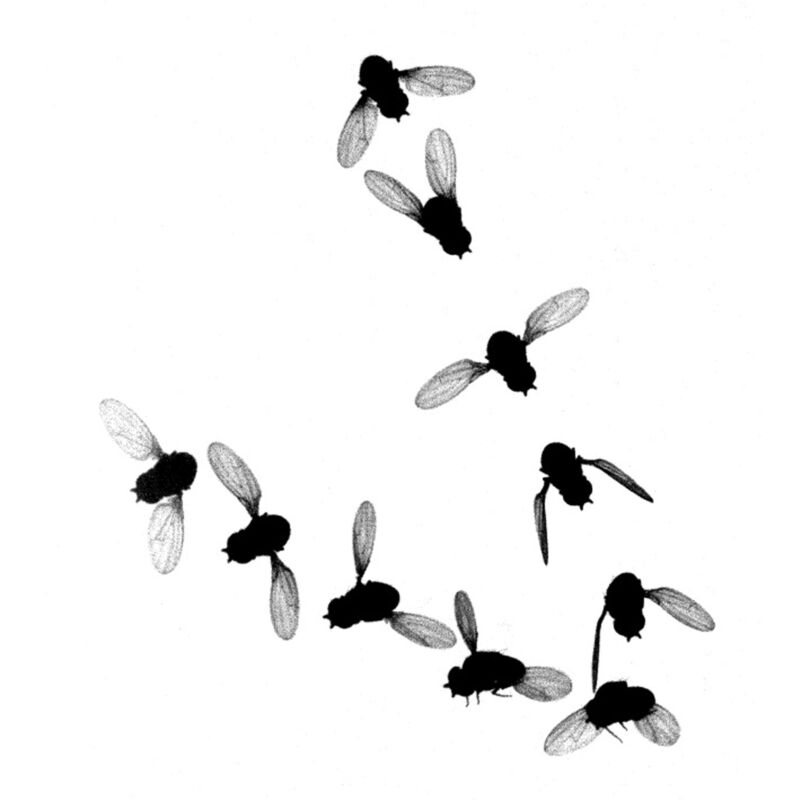

Enlarge / A time-lapse showing how an insect's wing adopts very specific positions during flight. (credit: Florian Muijres, Dickinson Lab)

About 350 million years ago, our planet witnessed the evolution of the first flying creatures. They are still around, and some of them continue to annoy us with their buzzing. While scientists have classified these creatures as pterygotes, the rest of the world simply calls them winged insects.

There are many aspects of insect biology, especially their flight , that remain a mystery for scientists. One is simply how they move their wings. The insect wing hinge is a specialized joint that connects an insect’s wings with its body. It’s composed of five interconnected plate-like structures called sclerites. When these plates are shifted by the underlying muscles, it makes the insect wings flap.

Until now, it has been tricky for scientists to understand the biomechanics that govern the motion of the sclerites even using advanced imaging technologies. “The sclerites within the wing hinge are so small and move so rapidly that their mechanical operation during flight has not been accurately captured despite efforts using stroboscopic photography, high-speed videography, and X-ray tomography,” Michael Dickinson, Zarem professor of biology and bioengineering at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), told Ars Technica.