-

chevron_right

chevron_right

A City on Mars: Reality kills space settlement dreams

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Monday, 20 November - 21:22 · 1 minute

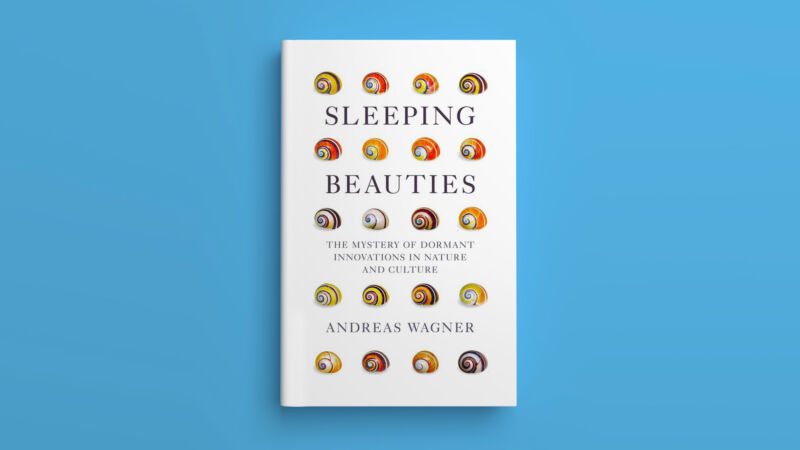

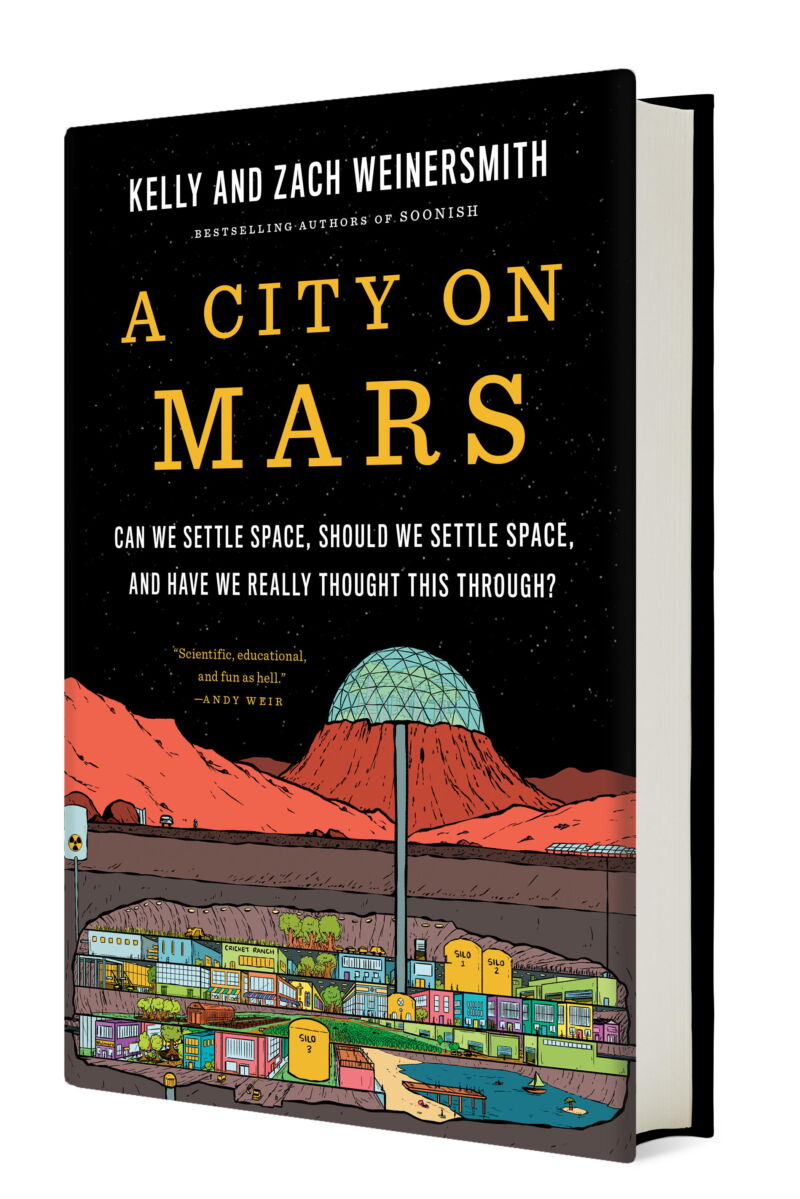

Enlarge (credit: Penguin Random House)

Let me start with the TLDR for A City on Mars . It is, essentially, 400 pages of "well, actually…," but without the condescension, quite a bit of humor, and many, oh so many, details. Kelly and Zach Weinersmith started from the position of being space settlement enthusiasts. They thought they were going to write a light cheerleading book about how everything was going to be just awesome on Mars or the Moon or on a space station. Unfortunately for the Weinersmiths, they actually asked questions like “how would that work, exactly?” Apart from rocketry (e.g., the getting to space part), the answers were mostly optimistic handwaving combined with a kind of neo-manifest destiny ideology that might have given Andrew Jackson pause.

The Weinersmiths start with human biology and psychology, pass through technology, the law, and population viability and end with a kind of call to action. Under each of these sections, the Weinersmiths pose questions like: Can we thrive in space? reproduce in space? create habitats in space? The tour through all the things that aren’t actually known is shocking. No one has been conceived in low gravity, no fetuses have developed in low gravity, so we simply don’t know if there is a problem. Astronauts experience bone and muscle loss and no one knows how that plays out long term. Most importantly, do we really want to find this out by sending a few thousand people to Mars and hope it all just works out?

Then there are the problems of building a habitation and doing all the recycling. I was shocked to learn that no one really knows how to construct a long-term habitable settlement for either the Moon or Mars. Yes, there are lots of hand-wavy ideas about lava tubes and regolith shielding. But the details are just… not there. It reminds me of Europe’s dark days of depositing colonies on other people’s land. The stories of how unprepared the settlers were are sad, hilarious, and repetitive . And, now we learn that we are planning for at least one more sequel.