-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Why canned wine can smell like rotten eggs while beer and Coke are fine

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · 3 days ago - 22:02 · 1 minute

Enlarge (credit: BackyardProduction/Getty Images)

True wine aficionados might turn up their noses, but canned wines are growing in popularity, particularly among younger crowds during the summer months, when style often takes a back seat to convenience. Yet these same wines can go bad rather quickly, taking on distinctly displeasing notes of rotten eggs or dirty socks. Scientists at Cornell University conducted a study of all the relevant compounds and came up with a few helpful tips for frustrated winemakers to keep canned wines from spoiling. The researchers outlined their findings in a recent paper published in the American Journal of Enology and Viticulture.

“The current generation of wine consumers coming of age now, they want a beverage that’s portable and they can bring with them to drink at a concert or take to the pool,” said Gavin Sacks, a food chemist at Cornell. “That doesn’t really describe a cork-finished, glass-packaged wine. However, it describes a can very nicely.”

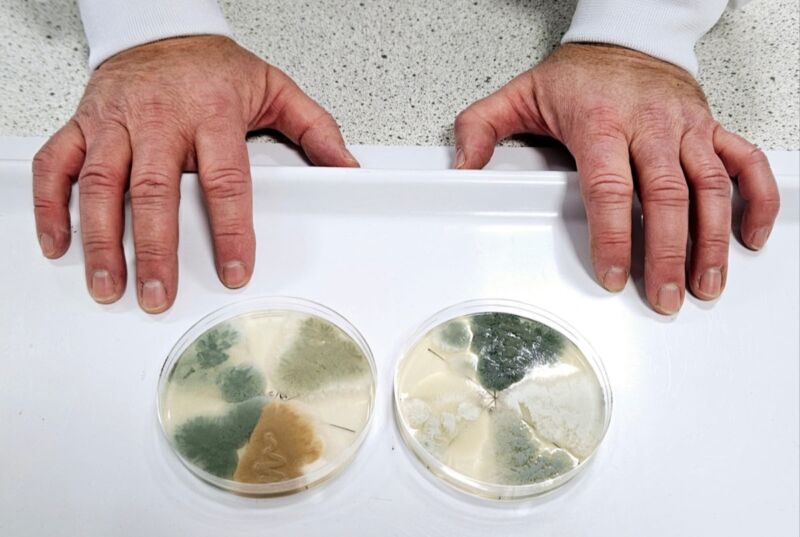

According to a 2004 article in Wine & Vines magazine, canned beer first appeared in the US in 1935, and three US wineries tried to follow suit for the next three years. Those efforts failed because it proved to be unusually challenging to produce a stable canned wine. One batch was tainted by " Fresno mold "; another batch resulted in cloudy wine within just two months; and the third batch of wine had a disastrous combination of low pH and high oxygen content, causing the wine to eat tiny holes in the cans. Nonetheless, wineries sporadically kept trying to can their product over the ensuing decades, with failed attempts in the 1950s and 1970s. United and Delta Airlines briefly had a short-lived partnership with wineries for canned wine in the early 1980s, but passengers balked at the notion.