-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Someone finally cracked the “Silk Dress cryptogram” after 10 years

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Tuesday, 30 January - 22:37 · 1 minute

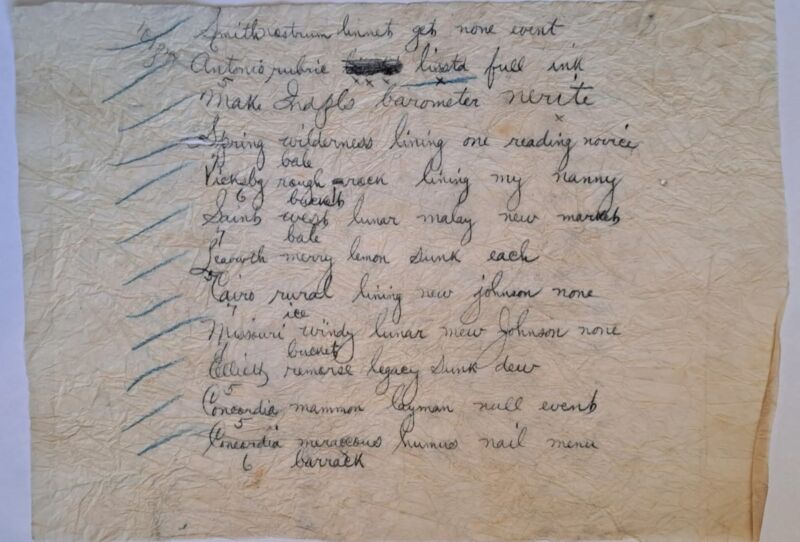

Enlarge / “Paul Ramify loamy event false new event” was one of the lines written on two sheets of paper found in a hidden pocket. (credit: Sara Rivers Cofield)

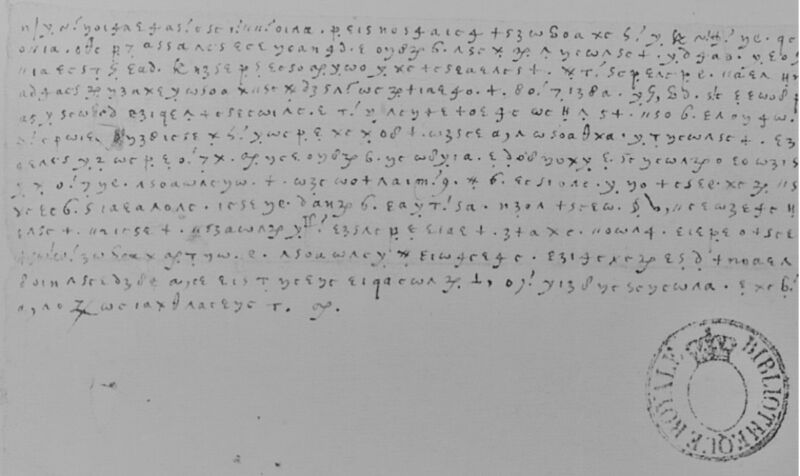

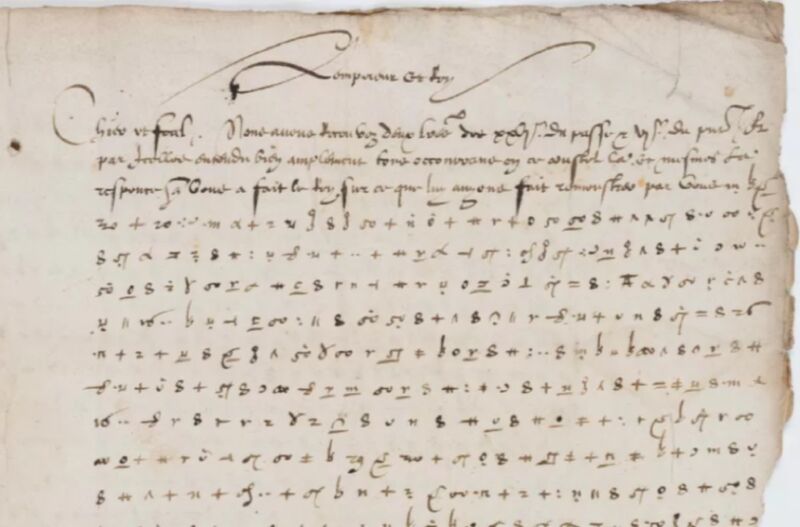

In December 2013, a curator and archaeologist purchased an antique silk dress with an unusual feature: a hidden pocket that held two sheets of paper with mysterious coded text written on them. People have been trying to crack the code ever since, and someone finally succeeded: University of Manitoba data analyst Wayne Chan. He discovered that the text is actually coded telegraph messages describing the weather used by the US Army and (later) the weather bureau. Chan outlined all the details of his decryption in a paper published in the journal Cryptologia.

“When I first thought I cracked it, I did feel really excited,” Chan told the New York Times. “It is probably one of the most complex telegraphic codes that I’ve ever seen.”

Sara Rivers-Cofield purchased the bronze-colored silk bustle dress with striped rust velvet accents for $100 at an antique shop in Maine, noting on her blog that it was in a style that was fashionable in the mid-1880s among middle-class or well-off women. There wasn't any fitted boning in the bodice, so the dress was meant to be worn with a corset. It had a draped skirt and bustle with metal buttons decorated with an "Ophelia motif." While the dress had been machine-stitched, the original buttons had been sewn by hand. A tag with the name "Bennett" was sewn into the bodice.