-

chevron_right

MPA: Site-Blocking Will Stop Pirate Site Owners Who Abuse Kids & Traffick Drugs

news.movim.eu / TorrentFreak · Wednesday, 10 April - 17:45 · 9 minutes

It’s no secret that the Motion Picture Association (MPA) views site-blocking measures in the United States as the logical next step in their perpetual campaign against piracy.

It’s no secret that the Motion Picture Association (MPA) views site-blocking measures in the United States as the logical next step in their perpetual campaign against piracy.

Working with U.S. Congress members, the plan is to propose judicial site-blocking legislation that will see local ISPs compelled by law to prevent consumer access to pirate sites. A similar but broader effort failed in 2012 but twelve years is a very long time; in the tech and internet world, it’s almost forever.

In the years since the rise and fall of SOPA, the MPA has been the driving force behind site-blocking legislation around the world, modeling dozens of partner countries in the shape of its vision for blocking in the U.S.

At this year’s CinemaCon ‘State of the Industry’ event at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, MPA Chairman and CEO Charles Rivkin said that the United States now has plenty of catching up to do.

“It’s long past time to bring out laws in line with the rest of the world,” Rivkin said, a reference to the MPA’s substantial body of overseas work it now hopes to replicate back home.

Preparation for the Big Site-Blocking Push

After reliving the high points of 2023 – Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon and the portmanteau of the moment, Barbenheimer – Rivkin turned to the bottom line. The MPA’s top man reported box office revenues in the U.S. and Canada up 20 percent on the previous year, and up nearly 30 percent abroad. An unquestionably great achievement, especially without protection from site-blocking.

But while tradition allows for generous helpings of creative imagery in support of the magical silver screen, financial positives are dwelled upon only fleetingly; the fairy dust is quickly dispersed, bringing reality into sharp focus.

Commentary explaining why the figures aren’t as good as they sound, or will take great effort to maintain, helps to calibrate expectations. After assuring everyone they’re in this together, and whatever needs to be done will be done, because that’s what Hollywood does, the groundwork to support demands for new legislation are carefully laid.

It’s a tried and tested system that really does work; Rocky Balboa’s unbreakable determination in 2021 mid-COVID, a home/mobile entertainment market up 24 percent in 2022 and a billion at the box office in the first quarter. Avatar: The Way of Water surging past $2.3 billion in global ticket sales, Top Gun: Maverick at $1.5 billion and still plenty of jet fuel left in the tank.

Then a short pause as the tension builds for the annual stark reminder; American creators are under attack, just as they were last year, the year before, and every year before that.

We have no illusions about the scope and the severity of the problem……The challenges are as daunting as they are uncertain….. One of the biggest existential threats to our collective future.

Used during the last three CinemaCons, the warnings above won’t be enough this year. Not at a time when Congress is listening.

Piracy is Visible, Behind The Scenes Lies Worse

Piracy rhetoric usually finds itself delivered in a way that counters notions of stability based on reported business successes. When an urgent drive for new legislation is imminent, there’s no room for complacency and at CinemaCon the nature of the threat left nothing to the imagination.

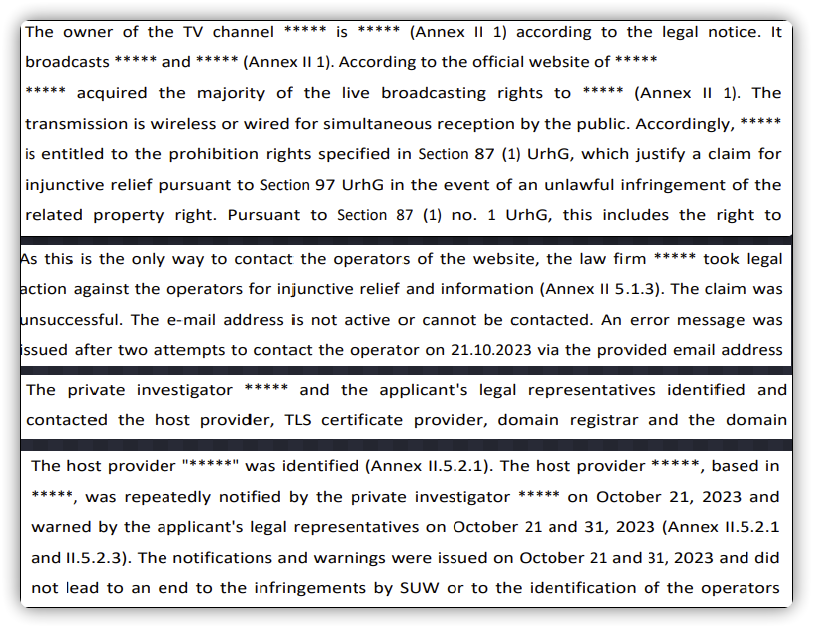

“Remember, these aren’t teenagers playing an elaborate prank. The perpetrators are real-life mobsters, organized crime syndicates, many of whom engage in child pornography, prostitution, drug trafficking, and other societal ills,” Rivkin informed the audience.

And it’s not just big companies facing immediate threat; the entire country is at risk.

“They operate websites that draw in millions of unsuspecting viewers whose personal data can then fall prey to malware and hackers,” Rivkin said. “In short, piracy is clearly not a victimless crime.”

People shouldn’t go about their work in fear, however. They should listen to a story first.

Telling a Compelling Story

Rivkin told CinemaCon that the MPA focuses on two pillars: Protecting content and the people who produce it, which together pave the way for the industry to reach even bigger audiences worldwide.

“To make that happen, we need to keep doing what we do best: telling a compelling story,” the head of the MPA explained.

“When I head to Capitol Hill in DC or State Capitols throughout the country, for example, I paint a picture of the ways our productions bolster communities: how film and television support 2.74 million American jobs; how production comprises 122,000 businesses; and how our incredible industry boasts a trade surplus with nearly every nation on earth.

Today, our job involves another plotline countering a central threat to the security of workers, audiences, and the economy at large: Widespread, digital piracy.

“This problem isn’t new. But piracy operations have only grown more nimble, more advanced, and more elusive. These enterprises are engaged in insidious forms of theft, breaking laws each time they steal and share protected content. These activities are nefarious by any definition, detrimental to our industry by any standard, and dangerous for the rights of creators and consumers by any measure,” Rivkin warnned.

Mobsters, organized crime syndicates, child pornographers, prostitution, drug trafficking, malware and hackers. Hundreds of thousands of jobs stolen from workers and tens of billions of dollars from the U.S. economy, “including more than one billion in theatrical ticket sales.”

As stories go, it’s as compelling as a synopsis accompanying a good film on Netflix which promises and then delivers, exactly as advertised. Or a bad one, where the exciting stuff appears in the synopsis yet somehow never makes it into the movie.

Regardless, the MPA has a plan, one that will protect content, protect creators, return a potential one billion dollars to theaters, and by extension, keep all Americans safe.

Blocking Piracy Websites

As outlined directly to the audience at CinemaCon: The MPA’s Site-Blocking Plan.

So today, here with you at CinemaCon, I’m announcing the next major phase of this effort: the MPA is going to work with Members of Congress to enact judicial site-blocking legislation here in the United States.

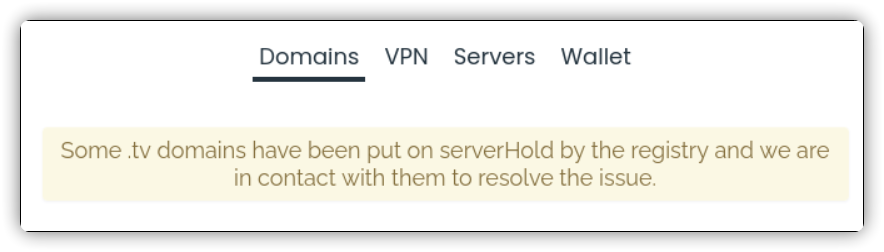

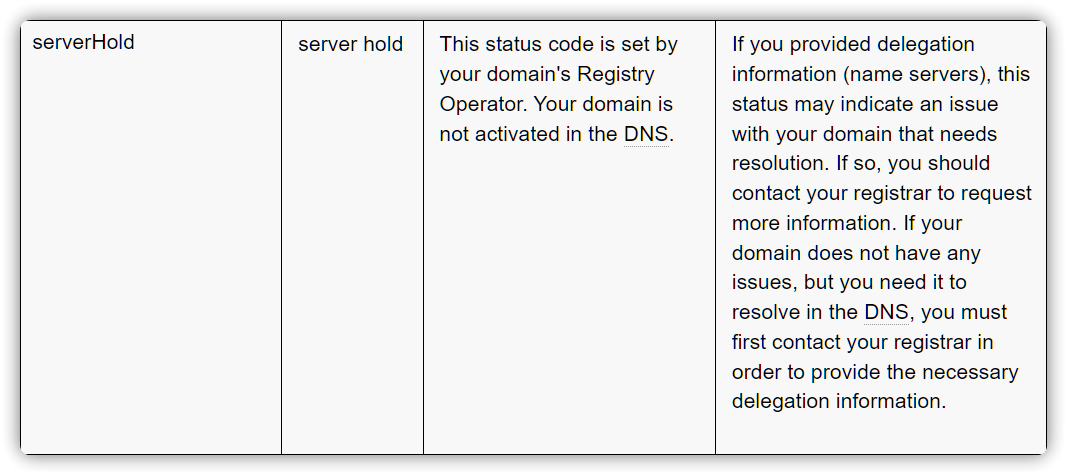

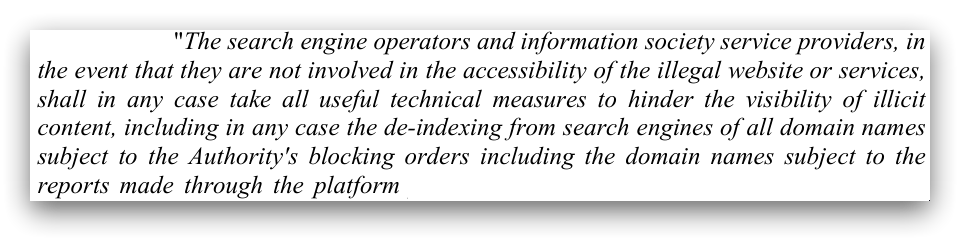

For anybody unfamiliar with the term, site-blocking is a targeted, legal tactic to disrupt the connection between digital pirates and their intended audience. It allows all types of creative industries – film and television, music and book publishers, sports leagues and broadcasters – to request, in court, that internet service providers block access to websites dedicated to sharing illegal, stolen content.

Let’s be clear: this approach focuses only on sites featuring stolen materials. There are no gray areas here. Site-blocking does not impact legitimate businesses or ordinary internet users. To the contrary: it protects them, too.

And it does so within the bounds of due process, requiring detailed evidence establishing a target’s illegal activities and allowing alleged perpetrators to appear in a court of law. This is not an untested concept.

Site-blocking is a common tool in almost 60 countries, including leading democracies and many of America’s closest allies.

What key player is missing from that roster? Take a look at the map behind me. It’s us!

There’s no good reason for our glaring absence. No reason beyond a lack of political will, paired with outdated understandings of what site-blocking actually is, how it functions, and who it affects.

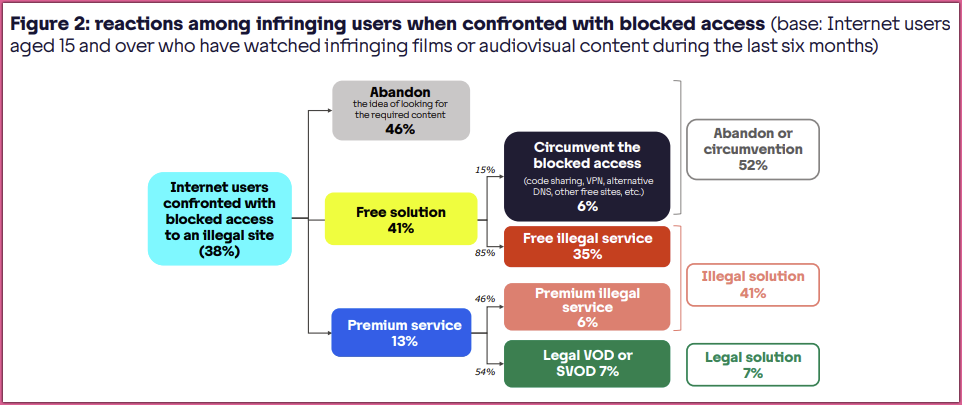

Yet experiences worldwide have now answered these concerns and taught us unmistakable lessons: Site-blocking works. It dramatically reduces traffic on piracy sites. It substantially increases visits to legal sites. Simply put, this is a powerful tool to defend what our filmmakers create and what reaches your theaters.

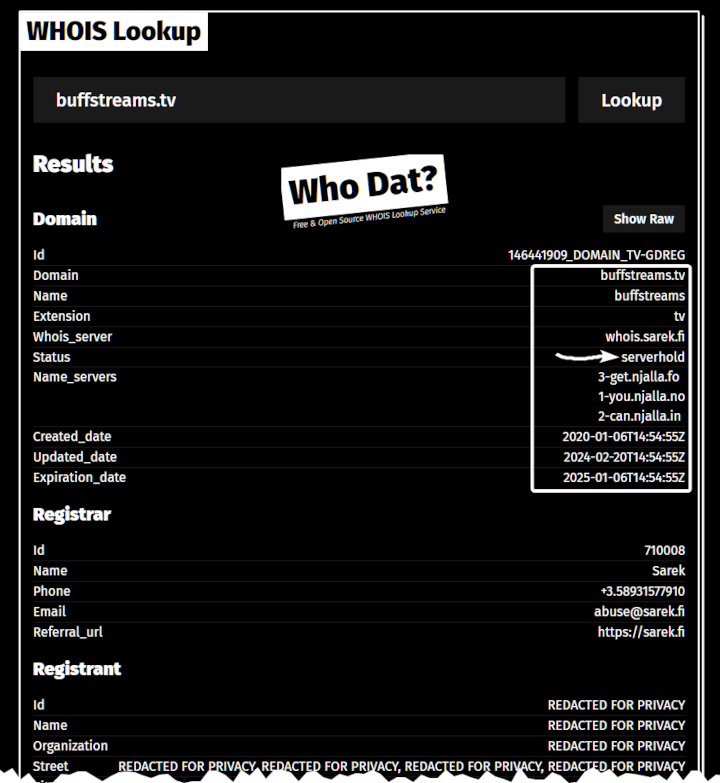

To show what site-blocking could achieve in the United States, Rivkin homed-in on a site that has thus far proved impossible to shut down, one that was highlighted in a House Subcommittee hearing last December .

FMovies Comment Reveals More Than Just Site-Blocking

There’s little doubt that FMovies represents a primary enforcement target for Hollywood, or rather it would be a target if authorities in Vietnam wanted to do something about it, which apparently they do not. While obviously a negative for Hollywood, when advocating for site-blocking legislation, FMovies is a lobbying gift on a golden platter.

“One of the largest illegal streaming sites in the world, FMovies, sees over 160 million visits per month and because other nations already passed site blocking legislation, a third of that traffic still comes from the United States”, Rivkin explained.

The 160 million visits per month estimate seems conservative and may have been measured in February when the site experienced an unexplained dip. In January, FMovies received almost 198 million visits and in March, traffic was returning to normal levels of around 192 million visits per month.

However, Rivkin’s follow-up comment to the theater-focused audience at CinemaCon may be an indication that the MPA has more on its mind than just blocking.

“Imagine if those viewers couldn’t find pirated versions of films through a basic internet search . Imagine if they could only watch the latest great movies when they’re released in their intended destinations: your theaters. If we had site-blocking in place, we wouldn’t have to imagine it. We’d have another tool to make that real,” he said.

Memories of SOPA: “Blocking Didn’t Break The Internet”

Rivkin mentions the SOPA defeat in 2012 by citing one of the key claims by the opposition. They warned that eventually, one way or another, blocking would end up “breaking the internet” but a dozen years later, Rivkin noted that the “internet is doing just fine.”

While that is still likely to be a hot topic for debate in the coming months, Rivkin’s search engine comment deserves more attention.

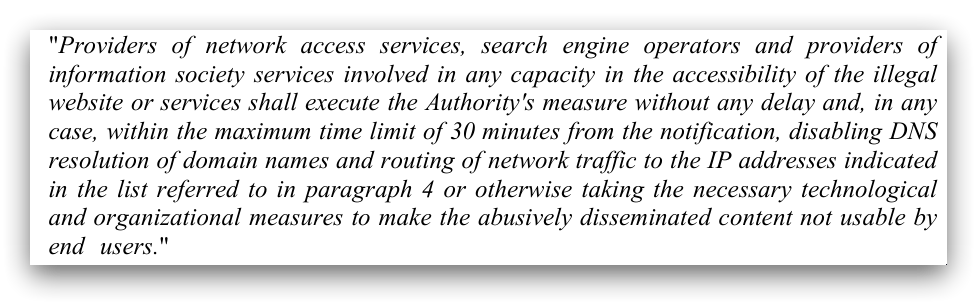

Search engine removals or deindexing by companies such as Google don’t automatically happen just because a site is blocked by ISPs in a particular territory. What we know from blocking in Europe is that Google will remove sites from its results if a blocking order exists against a site, even if Google isn’t named in the order. In the SOPA era, that would never have happened, and certainly not voluntarily.

Times Change, But By How Much?

In today’s environment, there seems to be no obvious obstacle to prevent Google from doing the same, should site-blocking become available in the United States. If that type of cooperation does become the standard, perhaps Google will cooperate when it comes to blocking sites that use its DNS too.

We don’t know what Google is thinking and it could go either way. What we suspect is that a re-run of 2012, with the entire tech world united in opposition to SOPA and blocking in general, seems much less likely today.

The MPA could tip the scales even further in its favor by telling more detailed stories about the real-life mobsters and organized crime syndicates behind pirate sites it will actually name, in public, with supporting evidence.

If not for the sake of Hollywood, bringing the child abuse, prostitution, and drug trafficking to an end might be the biggest PR coup ever seen. As the basis for a box office record-breaker in which Hollywood itself stars, would be all the more tempting, especially in the absence of piracy.

Image credit: Stockcake

From: TF , for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.