-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Why are there so many species of beetles?

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Sunday, 7 April - 11:02 · 1 minute

Enlarge (credit: Laurie Rubin via Getty )

Caroline Chaboo’s eyes light up when she talks about tortoise beetles. Like gems, they exist in myriad bright colors: shiny blue, red, orange, leaf green and transparent flecked with gold. They’re members of a group of 40,000 species of leaf beetles, the Chrysomelidae, one of the most species-rich branches of the vast beetle order, Coleoptera. “You have your weevils, longhorns, and leaf beetles,” she says. “That’s really the trio that dominates beetle diversity.”

An entomologist at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Chaboo has long wondered why the kingdom of life is so skewed toward beetles: The tough-bodied creatures make up about a quarter of all animal species. Many biologists have wondered the same thing, for a long time. “Darwin was a beetle collector,” Chaboo notes.

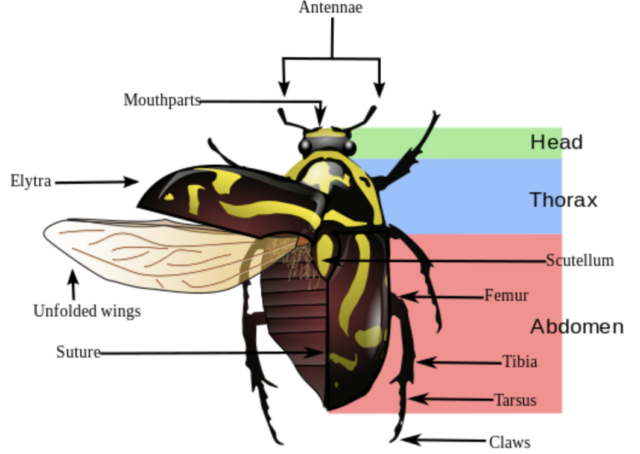

Despite their kaleidoscopic variety, most beetles share the same three-part body plan. The insects’ ability to fold their flight wings, origami-like, under protective forewings called elytra allows beetles to squeeze into rocky crevices and burrow inside trees. Beetles’ knack for thriving in a large range of microhabitats could also help explain their abundance of species, scientists say. (credit: Bugboy52.40 (CC BY-SA 3.0) via Wikimedia Commons )

Of the roughly 1 million named insect species on Earth, about 400,000 are beetles. And that’s just the beetles described so far. Scientists typically describe thousands of new species each year. So—why so many beetle species? “We don’t know the precise answer,” says Chaboo. But clues are emerging.