-

chevron_right

chevron_right

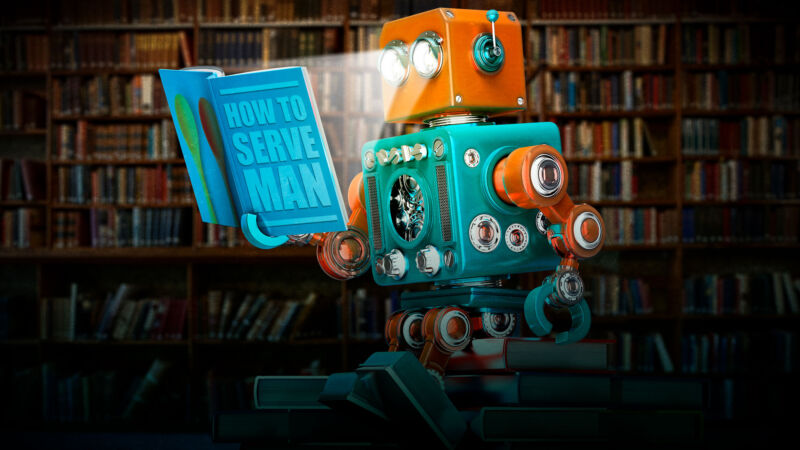

Producing more but understanding less: The risks of AI for scientific research

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Wednesday, 6 March - 18:08 · 1 minute

Enlarge / Current concerns about AI tend to focus on its obvious errors. But psychologist Molly Crockett and anthropologist Lisa Messeri argue that AI also poses potential long-term epistemic risks to the practice of science. (credit: Just_Super/E+ via Getty)

Last month, we witnessed the viral sensation of several egregiously bad AI-generated figures published in a peer-reviewed article in Frontiers, a reputable scientific journal. Scientists on social media expressed equal parts shock and ridicule at the images, one of which featured a rat with grotesquely large and bizarre genitals.

As Ars Senior Health Reporter Beth Mole reported , looking closer only revealed more flaws, including the labels "dissilced," "Stemm cells," "iollotte sserotgomar," and "dck." Figure 2 was less graphic but equally mangled, rife with nonsense text and baffling images. Ditto for Figure 3, a collage of small circular images densely annotated with gibberish.

The paper has since been retracted, but that eye-popping rat penis image will remain indelibly imprinted on our collective consciousness. The incident reinforces a growing concern that the increasing use of AI will make published scientific research less trustworthy, even as it increases productivity. While the proliferation of errors is a valid concern, especially in the early days of AI tools like ChatGPT, two researchers argue in a new perspective published in the journal Nature that AI also poses potential long-term epistemic risks to the practice of science.