ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

-

Pr

chevron_right

New Details Suggest Senior Trump Aides Knew Jan. 6 Rally Could Get Chaotic

pubsub.do.nohost.me / ProPublica · Friday, 25 June, 2021 - 09:00 · 23 minutes

On Dec. 19, President Donald Trump blasted out a tweet to his 88 million followers, inviting supporters to Washington for a “wild” protest.

Earlier that week, one of his senior advisers had released a 36-page report alleging significant evidence of election fraud that could reverse Joe Biden’s victory. “A great report,” Trump wrote. “Statistically impossible to have lost the 2020 Election. Big protest in D.C. on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!”

The tweet worked like a starter’s pistol, with two pro-Trump factions competing to take control of the “big protest.”

On one side stood Women for America First, led by Amy Kremer, a Republican operative who helped found the tea party movement. The group initially wanted to hold a kind of extended oral argument, with multiple speakers making their case for how the election had been stolen.

On the other was Stop the Steal, a new, more radical group that had recruited avowed racists to swell its ranks and wanted the President to share the podium with Alex Jones, the radio host banned from the world’s major social media platforms for hate speech, misinformation and glorifying violence. Stop the Steal organizers say their plan was to march on the Capitol and demand that lawmakers give Trump a second term.

ProPublica has obtained new details about the Trump White House’s knowledge of the gathering storm, after interviewing more than 50 people involved in the events of Jan. 6 and reviewing months of private correspondence. Taken together, these accounts suggest that senior Trump aides had been warned the Jan. 6 events could turn chaotic, with tens of thousands of people potentially overwhelming ill-prepared law enforcement officials.

Rather than trying to halt the march, Trump and his allies accommodated its leaders, according to text messages and interviews with Republican operatives and officials.

Katrina Pierson, a former Trump campaign official assigned by the White House to take charge of the rally planning, helped arrange a deal where those organizers deemed too extreme to speak at the Ellipse could do so on the night of Jan. 5. That event ended up including incendiary speeches from Jones and Ali Alexander, the leader of Stop the Steal, who fired up his followers with a chant of “Victory or death!”

The record of what White House officials knew about Jan. 6 and when they knew it remains incomplete. Key officials, including White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, declined to be interviewed for this story.

The second impeachment of President Trump focused mostly on his public statements, including his Jan. 6 exhortation that the crowd march on the Capitol and “fight like hell.” Trump was acquitted by the Senate, and his lawyers insisted that the attack on the Capitol was both regrettable and unforeseeable.

Rally organizers interviewed by ProPublica said they did not expect Jan. 6 to culminate with the violent sacking of the Capitol. But they acknowledged they were worried about plans by the Stop the Steal movement to organize an unpermitted march that would reach the steps of the building as Congress gathered to certify the election results.

One of the Women for America First organizers told ProPublica he and his group felt they needed to urgently warn the White House of the possible danger.

“A last-minute march, without a permit, without all the metro police that’d usually be there to fortify the perimeter, felt unsafe,” Dustin Stockton said in a recent interview.

“And these people aren’t there for a fucking flower contest,” added Jennifer Lynn Lawrence, Stockton’s fiancee and co-organizer. “They’re there because they’re angry.”

Stockton said he and Kremer initially took their concerns to Pierson. Feeling that they weren’t gaining enough traction, Stockton said, he and Kremer agreed to call Meadows directly.

Kremer, who has a personal relationship with Meadows dating back to his early days in Congress, said she would handle the matter herself. Soon after, Kremer told Stockton “the White House would take care of it,” which he interpreted to mean she had contacted top officials about the march.

Kremer denied that she ever spoke with Meadows or any other White House official about her Jan. 6 concerns. “Also, no one on my team was talking to them that I was aware of,” she said in an email to ProPublica. Meadows declined to comment on whether he’d been contacted.

A Dec. 27 text from Kremer obtained by ProPublica casts doubt on her assertion. Written at a time when her group was pressing to control the upcoming Jan. 6 rally, it refers to Alexander and Cindy Chafian, an activist who worked closely with Alex Jones. “The WH and team Trump are aware of the situation with Ali and Cindy,” Kremer wrote. “I need to be the one to handle both.” Kremer did not answer questions from ProPublica about the text.

So far, congressional and law enforcement reconstructions of Jan. 6 have established failures of preparedness and intelligence sharing by the U.S. Capitol Police, the FBI and the Pentagon, which is responsible for deploying the D.C. National Guard.

But those reports have not addressed the role of White House officials in the unfolding events and whether officials took appropriate action before or during the rally. Legislation that would have authorized an independent commission to investigate further was quashed by Senate Republicans.

Yesterday, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced she would create a select committee to investigate Jan. 6 that would not require Republican support. It’s not certain whether Meadows and other aides would be willing to testify. Internal White House dealings have historically been subject to claims of “executive privilege” by both Democratic and Republican administrations.

Our reporting raises new questions that will not be answered unless Trump insiders tell the story of that day. It remains unclear, for example, precisely what Meadows and other White House officials learned of safety concerns about the march and whether they took those reports seriously.

The former president has a well-established pattern of bolstering far-right groups while he and his aides attempt to maintain some distance. Following the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, Trump at first appeared to tacitly support torch-bearing white supremacists, later backing off. And in one presidential debate, he appeared to offer encouragement to the Proud Boys, a group of street brawlers who claim to protect Trump supporters, his statement triggering a dramatic spike in their recruitment. Trump later disavowed his support.

ProPublica has learned that White House officials worked behind the scenes to prevent the leaders of the march from appearing on stage and embarrassing the president. But Trump then undid those efforts with his speech, urging the crowd to join the march on the Capitol organized by the very people who had been blocked from speaking.

“And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore,” he said.

One Nation Under God

Ali Alexander during the Conservative Political Action Conference at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Maryland, on Feb. 28, 2019.

(Mark Peterson/Redux)

Ali Alexander during the Conservative Political Action Conference at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Maryland, on Feb. 28, 2019.

(Mark Peterson/Redux)

On Nov. 5, as Joe Biden began to emerge as the likely winner of the 2020 presidential election, a far-right provocateur named Ali Alexander assembled a loose collection of right-wing activists to help Trump maintain the presidency.

Alexander approached the cause of overturning the election with an almost messianic fervor. In private text messages, he obsessed over gaining attention from Trump and strategized about how to draw large, angry crowds in support of him.

On Nov. 7, the group held simultaneous protests in all 50 states.

Seven days later, its members traveled to Washington for the Million MAGA March, which drew tens of thousands. The event is now considered by many to be a precursor of Jan. 6.

Alexander united them under the battle cry “Stop the Steal,” a phrase originally coined by former Trump adviser Roger Stone, whom Alexander has called a friend. (Stone launched a short-lived organization of the same name in 2016.) To draw such crowds, Alexander made clear Stop the Steal would collaborate with anyone who supported its cause, no matter how extreme their views.

“We’re willing to work with racists,” he said on one livestream in December. Alexander did not return requests for comment made by email, by voicemail, to his recent attorney or to Stop the Steal PAC’s designated agent.

As he worked to expand his influence, Alexander found a valuable ally in Alex Jones, the conspiracy theorist at the helm of the popular far-right website InfoWars. Jones, who first gained notoriety for spreading a lie that the Sandy Hook school shooting was a hoax, had once counted more than 2 million YouTube subscribers and 800,000 Twitter followers before being banned from both platforms.

Alexander also collaborated with Nick Fuentes, the 22-year-old leader of the white nationalist “Groyper” movement.

“Thirty percent of that crowd was Alex Jones’ crowd,” Alexander said on another livestream, referring to the Million MAGA March on Nov. 14. “And there were thousands and thousands of Groypers — America First young white men. … Even if you thought these were bad people, why can’t bad people do good tasks? Why can’t bad people fight for their country?”

Nick Fuentes and Alex Jones during a Stop the Steal rally at the Georgia governor’s mansion on Nov. 19, 2020.

(Zach Roberts/NurPhoto/Getty Images)

Nick Fuentes and Alex Jones during a Stop the Steal rally at the Georgia governor’s mansion on Nov. 19, 2020.

(Zach Roberts/NurPhoto/Getty Images)

Alexander’s willingness to work with such people sparked conflict even within his inner circle.

“Is Nick Fuentes now a prominent figure in Stop the Steal?” asked Brandon Straka, an openly gay conservative activist, in a November text message, obtained exclusively by ProPublica. “I find him disgusting,” Straka said, pointing to Fuentes’ vehemently anti-LGBT views.

Alexander saw more people and more power. He wrote that Fuentes was “very valuable” at “putting bodies in places,” and that both Jones and Fuentes were “willing to push bodies … where we point.”

Straka, Fuentes and Jones did not respond to requests for comment.

Right-wing leaders who had once known each other only peripherally were now feeling a deeper sense of camaraderie. In an interview, Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio described how he felt as he walked alongside Jones through the crowds assembled in Washington on Nov. 14, after Jones had asked the Proud Boys to act as his informal bodyguards.

“That was the moment we really united everybody under one banner,” he said. “That everyone thought, ‘Fuck you, this is what we can do.’” According to Tarrio, the Proud Boys nearly tripled in numbers around this time, bringing in over 20,000 new members. “November was the seed that sparked that flower on Jan. 6,” he said.

Enrique Tarrio, leader of the Proud Boys, stands outside Harry’s bar in Washington, D.C., during a protest on Dec. 12, 2020.

(Stephanie Keith/Getty Images)

Enrique Tarrio, leader of the Proud Boys, stands outside Harry’s bar in Washington, D.C., during a protest on Dec. 12, 2020.

(Stephanie Keith/Getty Images)

The crowds impressed people like Tom Van Flein, chief of staff for Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Ariz. Van Flein told ProPublica he kept in regular contact with Alexander while Gosar led the effort in Congress to shoot down the election certification. “Ali was very talented and put on some very good rallies on short notice," Van Flein said. “Great turnout.”

But as Jan. 6 drew nearer, the Capitol Police became increasingly concerned by the disparate elements that formed the rank and file of the organization.

“Stop the Steal’s propensity to attract white supremacists, militia members, and others who actively promote violence, may lead to a significantly dangerous situation for law enforcement and the general public alike,” the Capitol Police wrote in a Jan. 3 intelligence assessment.

Yet the police force, for all its concern, wound up effectively blindsided by what happened on Jan. 6.

An intelligence report from that day obtained by ProPublica shows that the Capitol Police expected a handful of rallies on Capitol grounds, the largest of which would be hosted by a group called One Nation Under God.

Law enforcement anticipated between 50 and 500 people at the gathering, assigning it the lowest possible threat score and predicting a 1% to 5% chance of arrests. The police gave much higher threat scores to two small anti-Trump demonstrations planned elsewhere in the city.

However, One Nation Under God was a fake name used to trick the Capitol Police into giving Stop the Steal a permit, according to Stop the Steal organizer Kimberly Fletcher. Fletcher is president of Moms for America, a grassroots organization founded to combat “radical feminism.”

“Everybody was using different names because they didn’t want us to be there,” Fletcher said, adding that Alexander and his allies experimented with a variety of aliases to secure permits for the east front of the Capitol. Laughing, Fletcher recalled how the police repeatedly called her “trying to find out who was who.”

A Senate report on security failures during the Capitol riot released earlier this month suggests that at least one Capitol Police intelligence officer had suspicions about this deceptive strategy, but that leadership failed to appreciate it — yet another example of an intelligence breakdown.

On Dec. 31, the officer sent an email expressing her concerns that the permit requests were “being used as proxies for Stop the Steal” and that those requesting permits “may also be involved with organizations that may be planning trouble” on Jan. 6.

A Capitol Police spokesperson told ProPublica on April 2, “Our intelligence suggested one or more groups were affiliated with Stop the Steal,” after we asked for a copy of the One Nation Under God permit, which they declined to provide.

Yet 18 days later, Capitol Police Acting Chief Yogananda Pittman told congressional investigators that she believed the permit requests had been properly vetted and that they were not granted to anyone affiliated with Stop the Steal. Pittman did not respond to ProPublica requests for comment.

Last week, a Capitol Police spokesperson told ProPublica, “The Department knew that Stop the Steal and One Nation Under God organizers were likely associated,” but added that the police believed denying a permit based on “assumed associations” would be a First Amendment violation. “The Department did, however, take the likely association into account when making decisions to enhance its security posture.”

Kenneth Harrelson, an Oath Keeper who allegedly ran the far-right group’s “ground team” in D.C. on Jan. 6, went to Washington to provide security for Alexander, according to Harrelson’s wife. Harrelson has pleaded not guilty to felony charges in connection with the riot and is one of the Oath Keepers at the center of a major Department of Justice conspiracy case.

Harrelson’s wife, Angel Harrelson, said in an interview with ProPublica that her husband was excited to visit Washington for the first time, especially to provide security for an important person, but that he lost Alexander in the chaos that consumed the Capitol and decided to join the crowd inside.

Men belonging to the Oath Keepers wearing military tactical gear attend the Stop the Steal rally on Jan. 6 in Washington, D.C.

(Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images)

Men belonging to the Oath Keepers wearing military tactical gear attend the Stop the Steal rally on Jan. 6 in Washington, D.C.

(Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images)

“Historic Day!”

As the movement hurtled toward Jan. 6, what started as a loosely united coalition quickly splintered, dividing into two competing groups that vied for power and credit.

On one side, Alexander and Jones had emerged as a new, more extreme element within the Republican grassroots ecosystem.

Their chief opposition was the organization Women for America First, helmed by Kremer and other veterans of the tea party movement, itself once viewed as the Republican fringe. Kremer was an early backer of Trump, and her tea party work helped get Mark Meadows elected to the House of Representatives in 2012.

The schism was rooted in an ideological dispute. Kremer felt Alexander’s agenda and tactics were too extreme; Alexander wanted to distinguish Stop the Steal by being more directly confrontational than Kremer’s group and the tea party. “Our movement is masculine in nature,” he said in a livestream.

Trump promoted both groups’ events online at various times.

Stop the Steal, through its alias One Nation Under God, obtained a Capitol Police permit to rally on Capitol grounds, while Kremer and Women for America First controlled the National Park Service permit for a large gathering on the White House Ellipse.

Alexander and Jones wanted to speak at the Ellipse rally, but Kremer was opposed. The provocateurs found a powerful ally in Caroline Wren, an elite Republican fundraiser with connections to the Trump family, particularly Donald Trump Jr. and his partner, Kimberly Guilfoyle. Wren had raised money for the Ellipse rally and pushed to get Alexander and Jones on stage, according to six people involved in the Jan. 6 rally and emails reviewed by ProPublica.

Pierson, the Trump campaign official, had initially been asked by Wren to help mediate the conflict. But Pierson shared Kremer’s concern that Jones and Alexander were too unpredictable. Pierson and Wren declined to comment.

On Jan. 2, the fighting became so intense that Pierson asked senior White House officials how she should handle the situation, according to a person familiar with White House communications. The officials agreed that Alexander and Jones should not be on the stage and told Pierson to take charge of the event.

The next morning, Trump announced to the world that he would attend the rally at the Ellipse. “I will be there. Historic day!” he tweeted. This came as a surprise to both rally organizers and White House staff, each of whom told ProPublica they hadn’t been informed he intended to speak at the rally.

That same day, a website went live promoting a march on Jan. 6. It instructed demonstrators to meet at the Ellipse, then march to the Capitol at 1 p.m. to “let the establishment know we will fight back against this fraudulent election. … The fate of our nation depends on it.”

Alexander and his allies fired off these instructions across social media.

While Kremer and her group had held legally permitted marches at previous D.C. rallies and promoted all their events with the hashtag #marchfortrump, this time their permit specifically barred them from holding an “organized march.” Rally organizers were concerned that violating their permit could create a legal liability for themselves and pose significant danger to the public, said Stockton, a political consultant with tea party roots who spent weeks with Kremer as they held rallies across the country in support of the president.

Lawrence and Stockton’s fellow organizers contacted Pierson to inform her that the march was unpermitted, according to Stockton and three other people familiar with the situation.

While ProPublica has independently confirmed that senior White House officials, including Meadows, were involved in the broader effort to limit Alexander’s role on Jan. 6, it remains unclear just how far the rally organizers went to warn officials of their specific fears about the march.

Another source present for communications between Amy Kremer and her daughter and fellow organizer, Kylie Kremer, told ProPublica that on Jan. 3, Kylie Kremer called her mother in desperation about the march.

Amy Kremer, chair of Women for America First, speaks at the “Save America Rally.” in Washington on Jan. 6.

(Jacquelyn Martin/AP)

Amy Kremer, chair of Women for America First, speaks at the “Save America Rally.” in Washington on Jan. 6.

(Jacquelyn Martin/AP)

Kylie Kremer asked her mom to escalate the situation to higher levels of the White House, and her mother said she would work on it, according to the source, who could hear the conversation on speakerphone. “You need to call right now,” the source remembered the younger Kremer saying.

The source said that Kylie Kremer suggested Meadows as a person to contact around that time.

The source said that in a subsequent conversation, Amy Kremer told her daughter she would take the matter to Eric Trump’s wife, Lara Trump. The source said that Kremer was in frequent contact with Lara Trump at the time.

Stockton said that he was not aware of Kremer talking to the family about Jan. 6, but added that Kremer regularly communicates with the Trump family, including Lara Trump. He also said that Kremer gave him the distinct impression that she had contacted Meadows about the march.

Through his adviser Ben Williamson, Meadows declined to comment on whether the organizers contacted him regarding the march.

Lara Trump, who spoke at the Ellipse on Jan. 6, did not immediately respond to a voicemail and text message asking for comment or to an inquiry left on her website. Eric Trump did not immediately respond to an emailed request for comment.

Lara and Eric Trump greet the crowd on the stage during the “Save America Rally” on Jan. 6.

(Photo by Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Lara and Eric Trump greet the crowd on the stage during the “Save America Rally” on Jan. 6.

(Photo by Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Kremer did not answer questions from ProPublica about communications with Lara Trump. Donald Trump’s press office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The White House, at the time, was scrambling from one crisis to the next. On Jan. 2, Trump and Meadows called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. Trump pressed Raffensperger to “find 11,780 votes” that would swing the state tally his way. On Jan. 3, the president met with Acting Secretary of Defense Christopher Miller and urged him to do what he could to protect Trump’s supporters on the 6th.

Meanwhile, Wren, the Republican fundraiser, was continuing to advocate for Jones and Alexander to play a prominent role at the Ellipse rally, according to emails and multiple sources.

A senior White House official suggested to Pierson that she resolve the dispute by going to the president himself, according to a source familiar with the matter.

On Jan. 4, Pierson met with Trump in the Oval Office. Trump expressed surprise that other people wanted to speak at the Ellipse at all. His request for the day was simple: He wanted lots of music and to limit the speakers to himself, some family members and a few others, according to the source and emails reviewed by ProPublica. The president asked if there was another venue where people like Alexander and Roger Stone could speak.

Pierson assured him there was. She informed the president that there was another rally scheduled the night before the election certification where those who lost their opportunity to speak at the Ellipse could still do so. It was meant as an olive branch extended between the competing factions, according to Stockton and two other sources.

Chafian, a reiki practitioner who’d been working closely with Alex Jones, was put in charge of the evening portion of the Jan. 5 event.

The speakers included Jones, Alexander, Stone, Michael Flynn and Three Percenter militia member Jeremy Liggett, who wore a flak jacket and led a “Fuck antifa!” chant. (Liggett is now running for Congress.) Chafian had invited Proud Boy leader Tarrio to speak as well, but Tarrio was arrested the day before on charges that he had brought prohibited gun magazines to Washington and burned a Black Lives Matter banner stolen from a church.

Former Trump campaign adviser Roger Stone, who was convicted of lying to Congress but later had his sentence commuted by President Trump, speaks at a pro-Trump rally at Washington’s Freedom Plaza on Jan. 5.

(Photo by Samuel Corum/Getty Images)

Former Trump campaign adviser Roger Stone, who was convicted of lying to Congress but later had his sentence commuted by President Trump, speaks at a pro-Trump rally at Washington’s Freedom Plaza on Jan. 5.

(Photo by Samuel Corum/Getty Images)

Tarrio told ProPublica that he did not know the flag was taken from a church and that the gun magazines were a custom-engraved gift for a friend. He has pleaded not guilty to a misdemeanor charge of property destruction; the gun magazine charge is still pending indictment before a grand jury.

“Thank you, Proud Boys!” Chafian shouted at the end of her speech. “The Proud Boys, the Oath Keepers, the Three Percenters — all of those guys keep you safe.”

Wren, however, would not back down. On the morning of Jan. 6, she arrived at the Ellipse before dawn and began arranging the seats. Jones and Alexander moved toward the front. Organizers were so worried that Jones and Alexander might try to rush the stage that Pierson contacted a senior White House official to see how aggressive she could get in her effort to contain Wren.

After discussing several options, the official suggested she call the United States Park Police and have Wren escorted off the premises.

Pierson relayed this to Kylie Kremer, who contacted the police. Officers arrived, but ultimately took no action.

By 9 a.m.,Trump supporters had arrived in droves: nuns and bikers, men in American flag suits, a line of Oath Keepers. Signs welcomed the crowd with the words “Save America March.”

Kylie Kremer greeted them gleefully. “What’s up, deplorables!” she said from the stage.

Wren escorted Jones and Alexander out of the event early, as they prepared to lead their march on the Capitol.

At 11:57 a.m, Trump got on stage and, after a rambling speech, gave his now infamous directive. “You’ll never take back our country with weakness. You have to show strength and you have to be strong,” he said. “I know that everyone here will soon be marching over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard.”

Lawrence, Dustin Stockton’s fiancee and co-organizer, remembers her shock.

“What the fuck is this motherfucker talking about?” Lawrence, an ardent Trump supporter, said of the former president.

In the coming hours, an angry mob would force its way into the building. Protesters smashed windows with riot shields stolen from cops, ransacked House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s chambers, and inflicted an estimated $1.5 million of damage. Roughly 140 police officers were injured. One was stabbed with a metal fence stake and another had spinal discs smashed, according to union officials.

The Stop the Steal group chat shows a reckoning with these events in real time.

“They stormed the capital,” wrote Stop the Steal national coordinator Michael Coudrey in a text message at 2:33 p.m. “Our event is on delay.”

“I’m at the Capitol and just joined the breach!!!” texted Straka, who months earlier had raised concerns about allying with white nationalists. “I just got gassed! Never felt so fucking alive in my life!!!”

Alexander and Coudrey advised the group to leave.

“Everyone get out of there,” Alexander wrote. “The FBI is coming hunting.”

In the months since, the Department of Justice has charged more than 400 people for their actions at the Capitol, including more than 20 alleged Proud Boys, over a dozen alleged Oath Keepers, and Straka. It’s unclear from court records whether Straka has yet entered a plea.

In emails to ProPublica, Coudrey declined to answer questions about Stop the Steal. “I just really don’t care about politics anymore,” he said. “It’s boring.”

Meadows, now a senior partner at the Conservative Partnership Institute, a think tank in Washington, appeared on Fox News on Jan. 27, delivering one of the first public remarks on the riot from a former Trump White House official. He encouraged the GOP to “get on” from Jan. 6 and focus on “what’s important to the American people.” Neither Meadows nor anyone else who worked in the Trump White House at the time has had to answer questions as part of the various inquiries currently proceeding in Congress.

Alexander has kept a low profile since Jan. 6. But in private, texts show, he has encouraged his allies to prepare for “civil war.”

“Don’t denounce anything,” he messaged his inner circle in January regarding the Capitol riot. “You don’t want to be on the opposite side of freedom fighters in the coming conflict. Veterans will be looking for civilian political leaders.”

Kirsten Berg and Lynn Dombek contributed additional reporting.

June 28, 2021: A caption with this story originally misstated the action President Donald Trump took to prevent Roger Stone from serving prison time. Trump commuted Stone’s sentence, not his conviction.

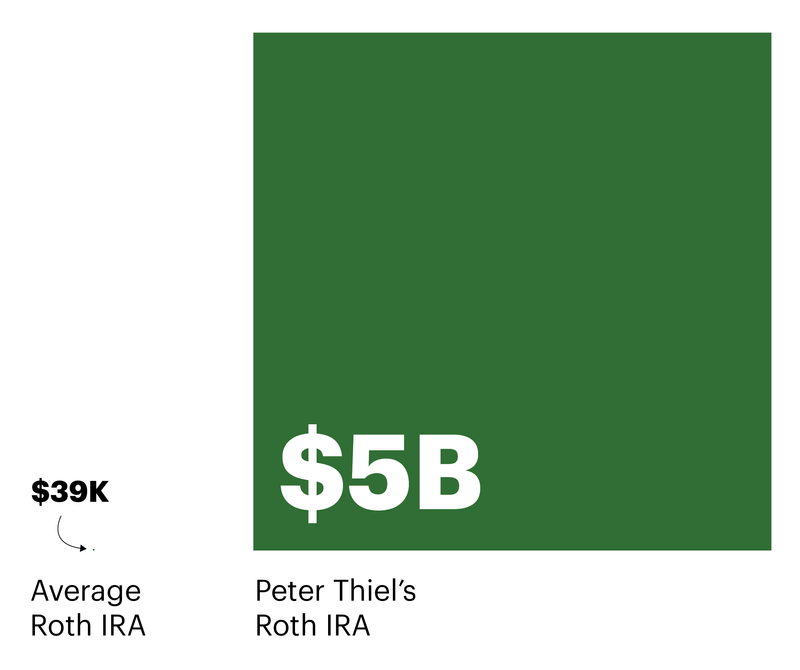

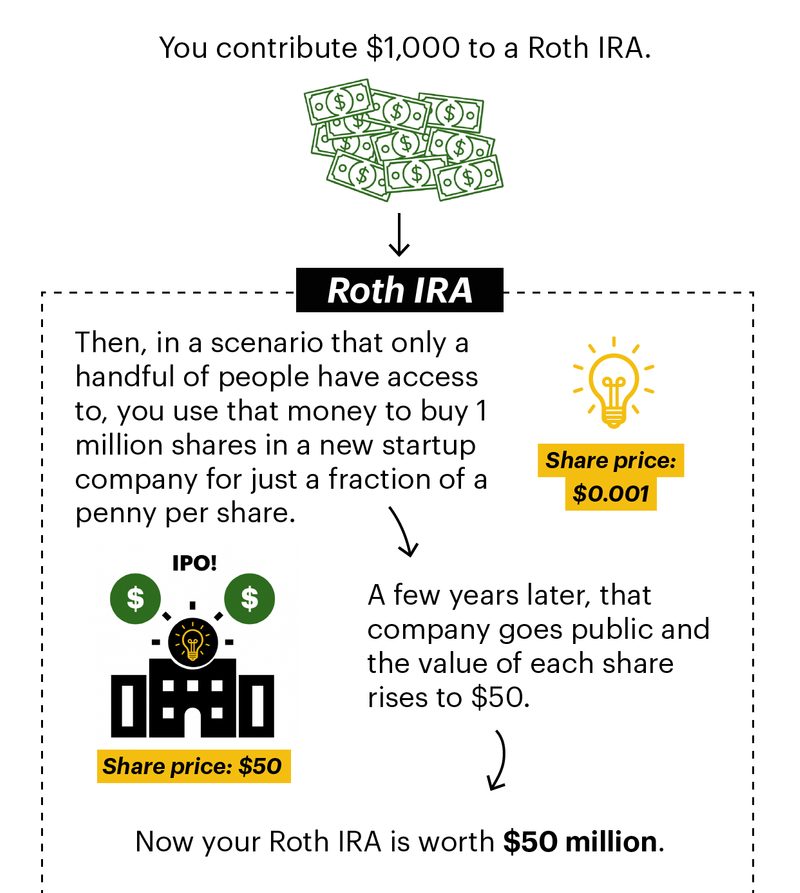

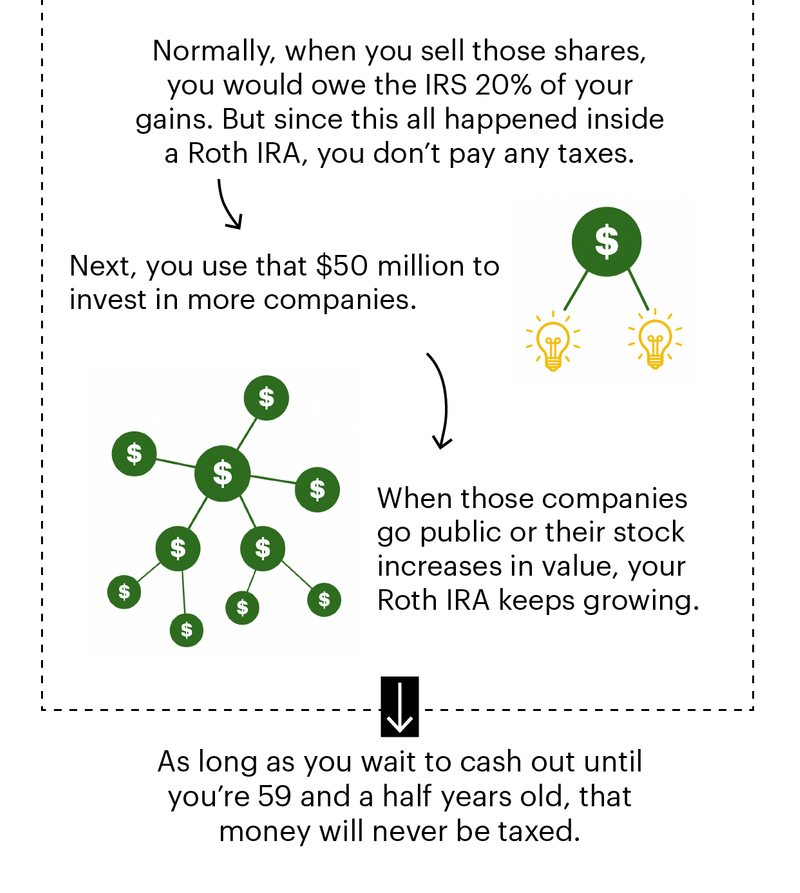

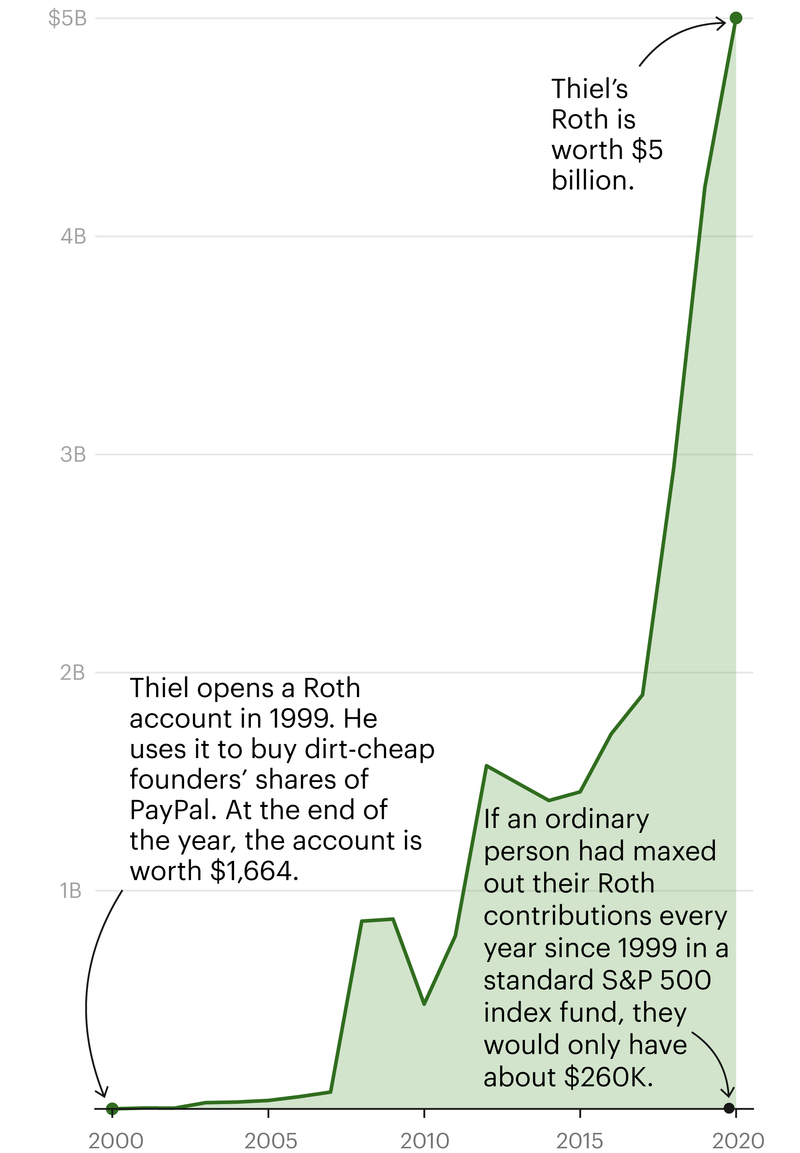

Source: ProPublica analysis of tax records, SEC filings and court documents.

Source: ProPublica analysis of tax records, SEC filings and court documents.

A Uyghur store owner criticizes the U.S. State Department’s declaration of genocide in Xinjiang. He says his experience in an “education and training center” removed his “religious extremist thoughts.”

A Uyghur store owner criticizes the U.S. State Department’s declaration of genocide in Xinjiang. He says his experience in an “education and training center” removed his “religious extremist thoughts.”

ProPublica and The New York Times analyzed propaganda videos featuring Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities from across Xinjiang.

ProPublica and The New York Times analyzed propaganda videos featuring Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities from across Xinjiang.

Many people in the videos use the expression tusheng-tuzhang (土生土长), meaning “born and raised.” They claim that, as native Xinjiangers, they know best how their community is treated.

Many people in the videos use the expression tusheng-tuzhang (土生土长), meaning “born and raised.” They claim that, as native Xinjiangers, they know best how their community is treated.

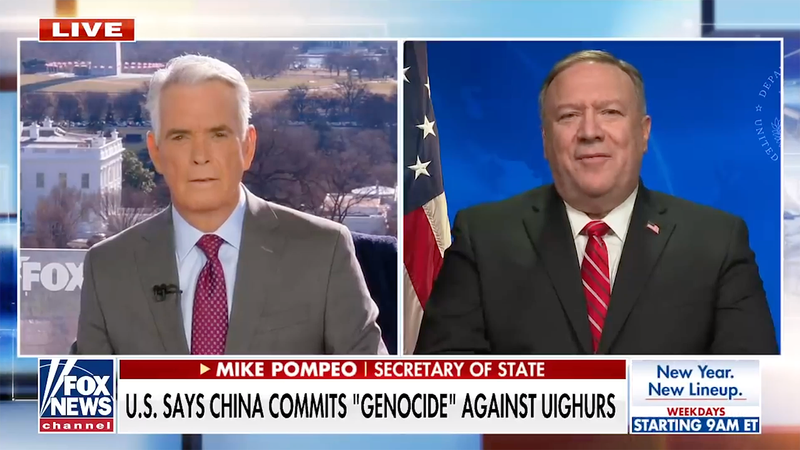

Many of those who appear in the videos claim to have recently seen former U.S. secretary of state Mike Pompeo’s declaration of genocide in Xinjiang.

Many of those who appear in the videos claim to have recently seen former U.S. secretary of state Mike Pompeo’s declaration of genocide in Xinjiang.

People in the videos frequently use the expression hushuo-badao (胡说八道), meaning “complete nonsense” or “hogwash,” to dismiss Pompeo’s accusations.

People in the videos frequently use the expression hushuo-badao (胡说八道), meaning “complete nonsense” or “hogwash,” to dismiss Pompeo’s accusations.

A video featuring a man who later acknowledged that his video was made by local propaganda officials.

A video featuring a man who later acknowledged that his video was made by local propaganda officials.

Pompeo appears in a Jan. 19 interview about the State Department’s declaration of genocide in Xinjiang earlier that day.

Pompeo appears in a Jan. 19 interview about the State Department’s declaration of genocide in Xinjiang earlier that day.

Some of the posts by the coordinated Twitter accounts shared the same video with nearly identical messages.

Some of the posts by the coordinated Twitter accounts shared the same video with nearly identical messages.

Posts by the coordinated Twitter accounts sometimes contain traces of computer code.

Posts by the coordinated Twitter accounts sometimes contain traces of computer code.

In a widely reposted propaganda video, farmworkers deny accusations of forced labor.

In a widely reposted propaganda video, farmworkers deny accusations of forced labor.

The greenhouse video has been tweeted by officials from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The greenhouse video has been tweeted by officials from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

A separate ongoing video propaganda campaign denies reports of forced labor in Xinjiang’s cotton industry.

A separate ongoing video propaganda campaign denies reports of forced labor in Xinjiang’s cotton industry.

The campaign contains several different videos that feature Rebiya Kadeer’s granddaughters.

The campaign contains several different videos that feature Rebiya Kadeer’s granddaughters.

Left: Rebiya Kadeer outside her home in Fairfax, Virginia. Right: Framed photos of Kadeer’s imprisoned son and other members of her family.

Left: Rebiya Kadeer outside her home in Fairfax, Virginia. Right: Framed photos of Kadeer’s imprisoned son and other members of her family.

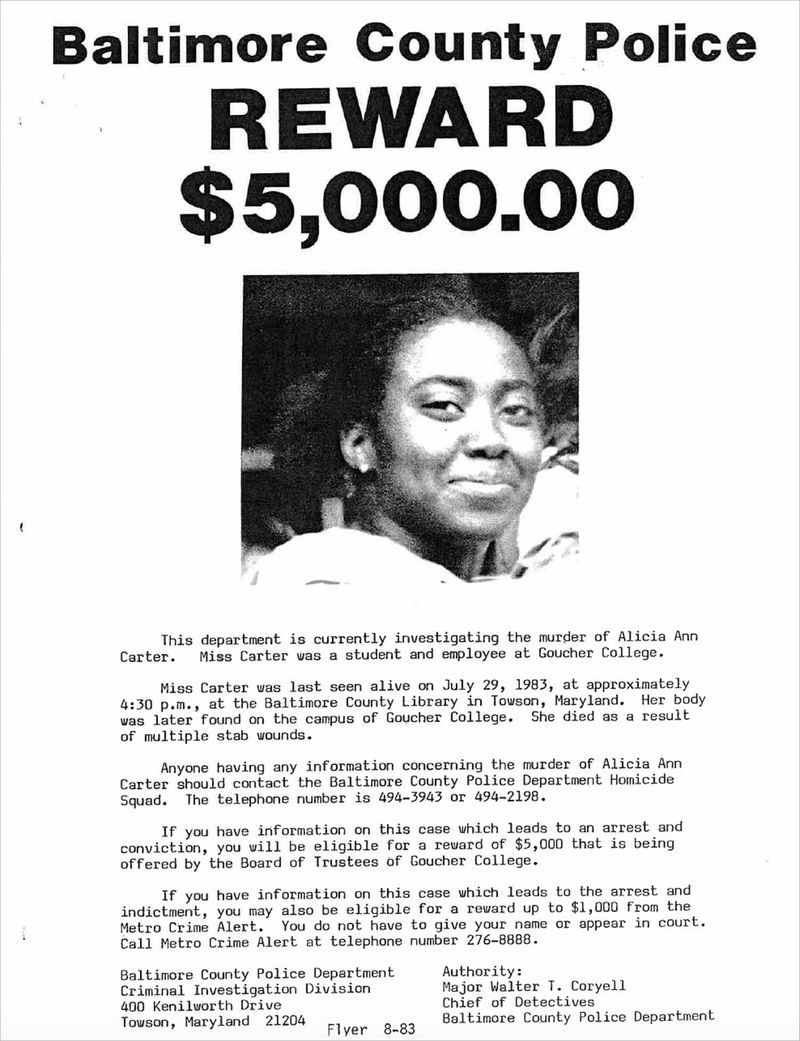

A 1983 poster offering a reward for information about Alicia Ann Carter’s murder.

A 1983 poster offering a reward for information about Alicia Ann Carter’s murder.