-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Event Horizon Telescope captures stunning new image of Milky Way’s black hole

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Wednesday, 27 March - 20:55 · 1 minute

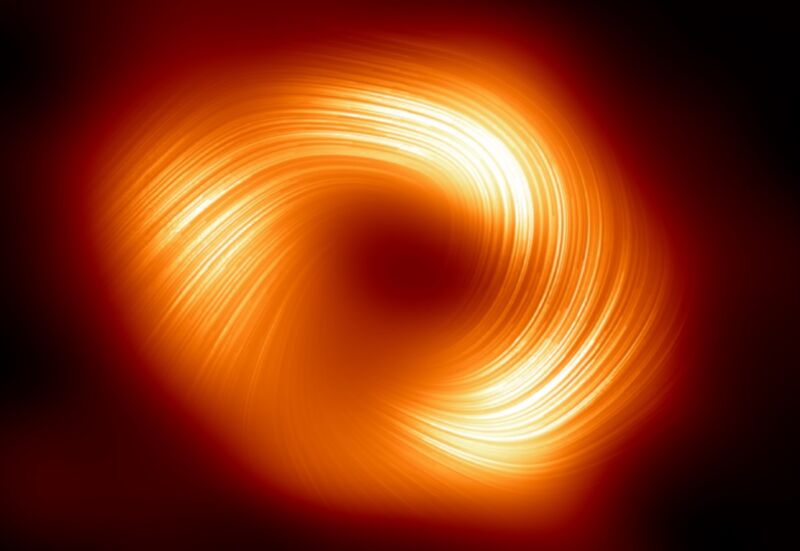

Enlarge / A new image from the Event Horizon Telescope has revealed powerful magnetic fields spiraling from the edge of a supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, Sagittarius A*. (credit: EHT Collaboration)

Physicists have been confident since the1980s that there is a supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, similar to those thought to be at the center of most spiral and elliptical galaxies. It's since been dubbed Sagittarius A* (pronounced A-star), or SgrA* for short. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) captured the first image of SgrA* two years ago. Now the collaboration has revealed a new polarized image (above) showcasing the black hole's swirling magnetic fields. The technical details appear in two new papers published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The new image is strikingly similar to another EHT image of a larger supermassive black hole, M87*, so this might be something that all such black holes share.

The only way to "see" a black hole is to image the shadow created by light as it bends in response to the object's powerful gravitational field. As Ars Science Editor John Timmer reported in 2019, the EHT isn't a telescope in the traditional sense. Instead, it's a collection of telescopes scattered around the globe. The EHT is created by interferometry, which uses light in the microwave regime of the electromagnetic spectrum captured at different locations. These recorded images are combined and processed to build an image with a resolution similar to that of a telescope the size of the most distant locations. Interferometry has been used at facilities like ALMA (the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) in northern Chile, where telescopes can be spread across 16 km of desert.

In theory, there's no upper limit on the size of the array, but to determine which photons originated simultaneously at the source, you need very precise location and timing information on each of the sites. And you still have to gather sufficient photons to see anything at all. So atomic clocks were installed at many of the locations, and exact GPS measurements were built up over time. For the EHT, the large collecting area of ALMA—combined with choosing a wavelength in which supermassive black holes are very bright—ensured sufficient photons.