One can only imagine the crew’s screams of pain when they discovered that a clerical error had robbed ‘Night of the Living Dead’ of its copyright protections.

One can only imagine the crew’s screams of pain when they discovered that a clerical error had robbed ‘Night of the Living Dead’ of its copyright protections.

George A. Romero’s masterpiece opened in 1968 to audiences largely unprepared for its genius. If anything, movie distributor Walter Reade Organization was even more unprepared.

The company’s failure to file for a new copyright after the movie ditched its original title ‘Night of the Flesh Eaters’ was the reason that Night of the Living Dead (NOLD) was quickly pushed into the public domain.

History has since shown us that due to the subsequent effect on the greater good, no suffering was in vain. NOLD inspired a whole genre of horror that has gained momentum with age. And for advocacy groups like the EFF, the story is

tailor-made for showing

how the public domain brings freedoms that can benefit society as a whole.

The EFF’s Q&A is very easy to understand and accurately reflects public domain theory, but nothing beats a generous dose of reality stomping all over the textbooks.

Night of the Copyright Claim

Last month a user of Reddit’s /r/copyright

revealed

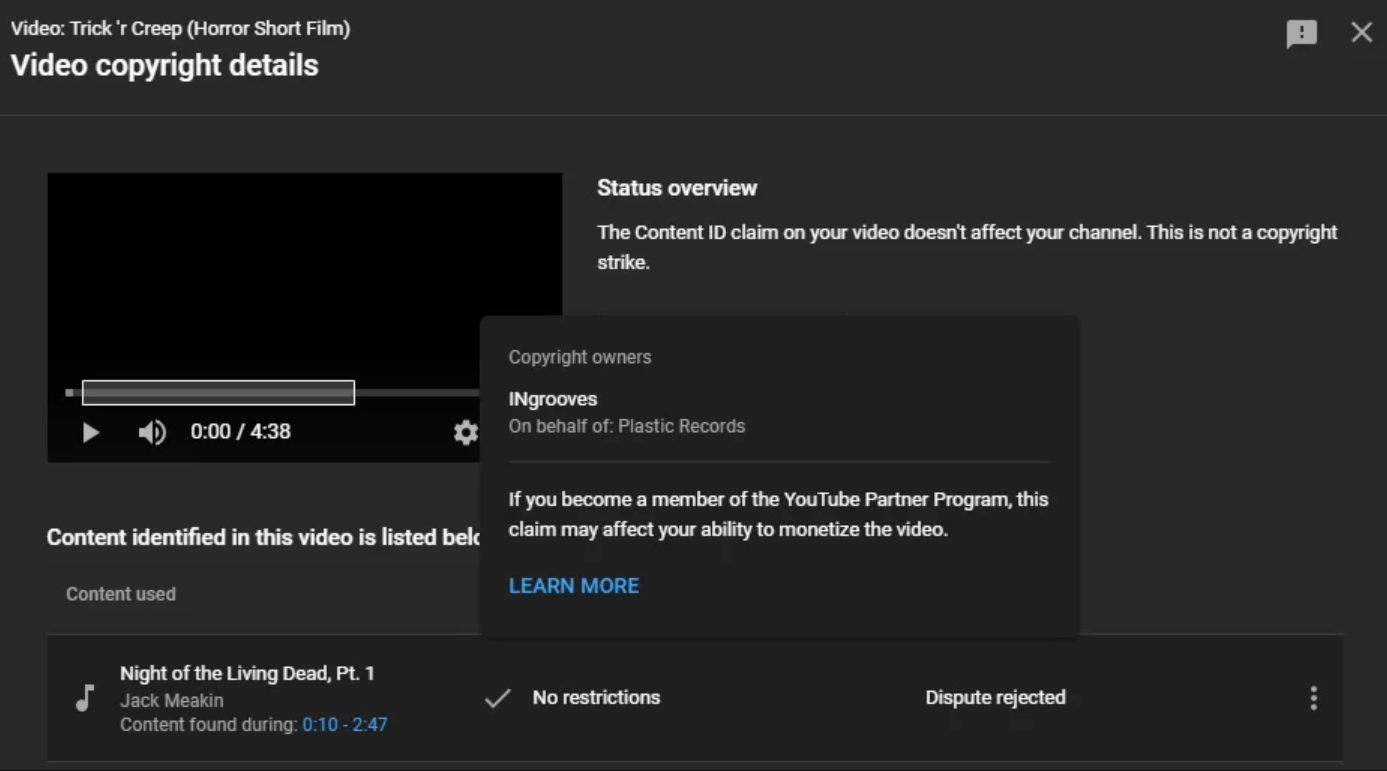

that they’d used some footage from NOLD in a short film titled ‘Trick ‘r Creep (Horror Short Film)’. After uploading the film to YouTube, the Google-owned video platform fired back a message, reporting that a portion of the video had been flagged due to the content being owned by a third party.

Since this was an automated Content ID claim, no strikes were involved, but how public domain content (specifically the NOLD soundtrack) was able to trigger the system in this way remained unclear. The YouTuber decided to contest the copyright claim, but YouTube quickly rejected it, leaving nowhere to go.

The image above shows that YouTube matched the user’s upload with another YouTube video titled ‘Night of the Living Dead, Pt. 1’, which was apparently uploaded by someone called Jack Meakin.

The Content ID notice lists the copyright owner as INgrooves, on behalf of Plastic Records, and the video they reportedly own is embedded below for reference.

What’s curious here is that

Jack Meakin’s YouTube channel

has just one subscriber and his NOLD video, which appears to contain 31 minutes of audio from the original movie, has a note underneath stating that the content was directly supplied to YouTube by Ingrooves.

There are no content match notices listed on this video, something that cannot be said about fan video

Night Of The Chopping Wood

, discussion video

Night of the Living Dead – Themes and Film Technique

, and countless partial or full uploads of NOLD.

All appear to have been identified by Content ID as matching the video on the Jack Meakin channel. The video contains audio from the 1968 public domain movie and is used as justification for Jack Meakin/Ingrooves to generate revenue from NOLD content uploaded by other YouTubers.

So Who Are These People and What Do They Want?

Ingrooves

is owned by Universal Music and describes itself as a global music distribution company providing marketing and rights management services for independent labels and artists.

Given the information provided in the Content ID notice, it seems possible that Ingrooves may represent Jack Meakin, who in turn might have some kind of arrangement with Plastic Records. While plausible, that fails to explain what connections these people have to public domain movie Night of the Living Dead, if any.

After we turned our focus to the mysterious Jack Meakin, a confusing situation somehow managed to get even more so. A Twitter search quickly turned up a

DJ/electronic musician

of the same name, but when we combined the name with the title of the movie, something even more unexpected entered the mix.

Jack Meakin Featuring George Romero

According to the

Living Dead wiki

, the music score of NOLD was not composed especially for the film but came from the libraries of WRS Studio and Capitol Records. Among the composers of that music was a man called Jack Meakin, who was born in 1906 and left for better things in 1982.

So was this the missing piece of the puzzle? Is it possible that the late Jake Meakin held some rights to his music in Night of the Living Dead? Were those rights passed to someone else after he passed away? If so, which of the compositions in the movie are his and why are Plastic Records involved, whoever they are?

We don’t have access to Content ID and given that YouTube is rejecting and refusing to discuss NOLD disputes, we decided to get a bit more creative. We found the Jack Meakin account on YouTube, hit play on the Night of the Living Dead video, fired up Shazam, and got a surprise instant hit.

According to our digital fingerprinting overlords, the piece is called ‘Chapter 1’ by a recording artist called ‘George Romero’. Wonderful…and thanks for nothing.

However, given that there are many links between Jack Meakin, George Romero and Night of the Living Dead on platforms other than YouTube, we turned our attention to Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon and general Google searches. There may be other things at play here but someone may have some explaining to do.

What Was That DJ on Twitter Called Again?

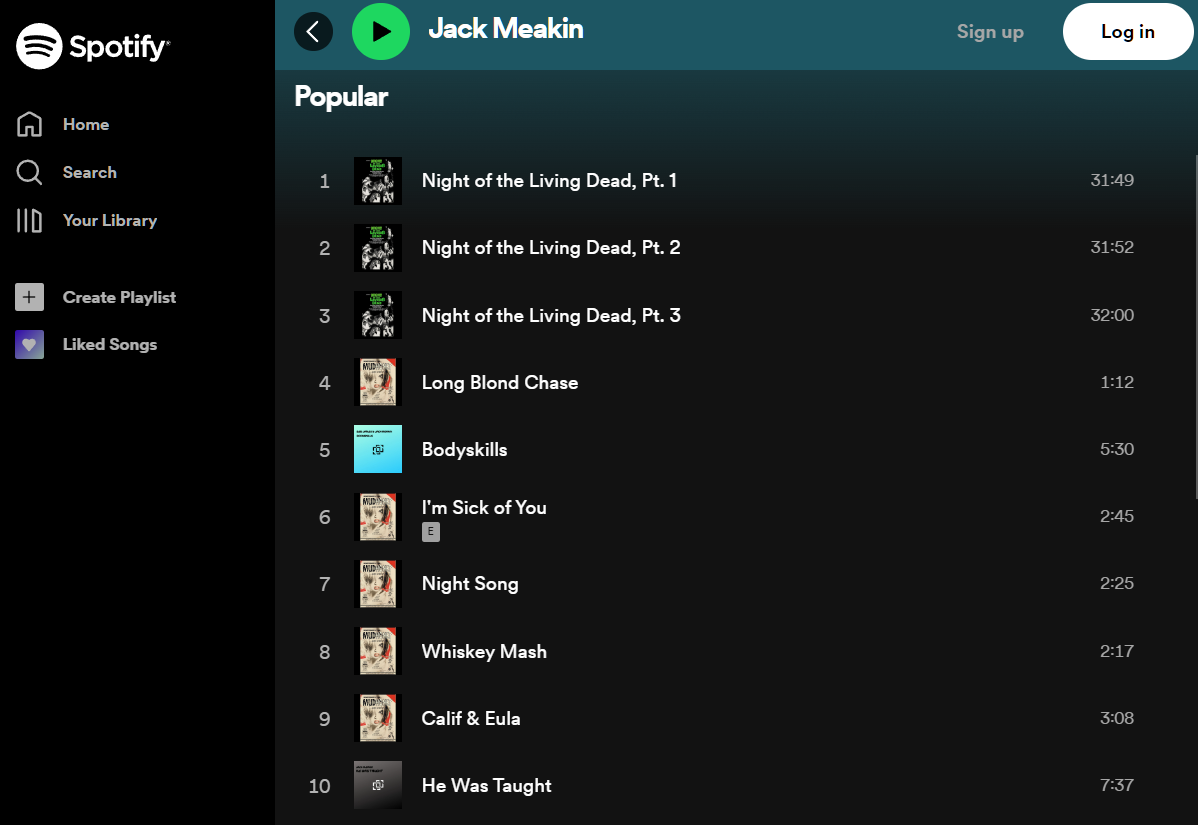

The Jack Meakin we completely disregarded on Twitter (because he’s a young DJ who didn’t even exist in 1968) is also a techno/trance producer. He has tracks including “He Was Taught” and “Bodyskills” available to stream on Apple, Spotify, and other similar platforms. He sometimes collaborates with Seb James, according to his Twitter account, but never mentions zombies publicly – at least far as we know.

Interestingly, DJ Jack Meakin is also credited with several other compositions. These include the whole soundtrack to Night of the Living Dead, which is available on dozens of other music platforms around the world, including

Apple Music

.

Conducting a

specific search

for Jack Meakin on Spotify not only turns up zombies but what appears to be some kind of musical Frankenstein.

Born in 1906, authorized to issue copyright claims on the most famous public domain horror movie of all time (years after his death), yet still spinning trance tracks at 116 years old – it’s the one and only (honestly)….Jack Meakin.

Anyone in need of additional proof that this incredible hybrid person really exists can check out the panel provided by Google alongside searches for Jack Meakin.

With other sites like

Discogs

identifying the actual NOLD composer by his full name (Jack Brunker Meakin) and describing him as an American musician, orchestra leader, and film composer from Salt Lake City, someone has led Google to believe that Jack Meakin is an actor in two movies and also a composer in the Dance/Electronic genre.

TorrentFreak attempted to reach the only Jack Meakin who could possibly respond in person but despite emails sent to him and his record label, we have discovered no signs of life. Appropriate if nothing else.

As a result, we still cannot explain why a company owned by Universal is monetizing Night of the Living Dead on behalf of a man who has been dead for 40 years, under the name of a living man who just happens to share his name. But we could have a wild guess.

Is it even plausible that someone in the music business simply ticked the wrong box in error and inadvertently merged two artists’ existences to create a single undead-like entity, one with a hunger so great it can only be satisfied by automatically feasting on public domain works? Or did someone accidentally upload and attribute the NOLD soundtrack to DJ Meakin?

We honestly have no idea but one thing seems certain. Someone has commissioned YouTube’s Content ID to target regular YouTubers using a public domain work in good faith, and then sent them messages implying or even stating that they had no right to do so. Then, to remedy this supposed infringement of someone’s rights, they’re now taking all the money.

Nice scheme? Looks like a no-brainer.

From:

TF

, for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.

chevron_right

Last year, YouTube released its first-ever copyright transparency report.

Last year, YouTube released its first-ever copyright transparency report.