-

chevron_right

chevron_right

The complicated history of how the Earth’s atmosphere became breathable

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Monday, 15 May, 2023 - 11:30

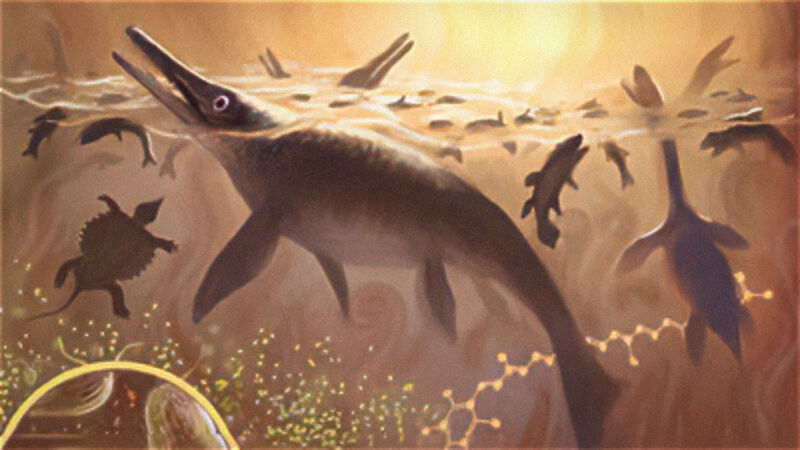

Enlarge (credit: Aurich Lawson | Getty Images)

The Great Oxygenation Event , which occurred around 2.4 billion years ago, was one of the biggest transformations of our planet. Before it, there was practically no oxygen in the atmosphere; after, there was.

Conventionally, the rise of oxygen is seen as life triumphantly terraforming a passive planet. But we’re learning now that Earth was an active participant, and it took two more big lifts of oxygen over the succeeding 2 billion years before it reached breathable levels. So which was more responsible for oxygen’s rise on Earth: the evolution of life or the evolution of the planet? Nature or nurture? And does the same answer apply to all of the rises of oxygen in Earth’s past?

It’s a question beyond curiosity about our past, as it also affects how we might interpret signs of life on exoplanets.