-

chevron_right

chevron_right

New animal family tree places us closer to weird disk-shaped organisms

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Wednesday, 17 May, 2023 - 18:38 · 1 minute

Enlarge / These complex creatures seem to be the earliest branch of the animal tree. We're more closely related to sponges than we are to them. (credit: Getty Images )

Ask someone to think of an animal, and chances are they'll come up with one of our relatives among the mammals. A few people might go further afield and mention other vertebrates, like birds and fish. But these barely scratch the surface of animal diversity, with things like cephalopods, insects, and echinoderms all having distinct features.

And that's before you get to the really weird stuff, like the radially symmetric Cnidarians, or the sponges that lack muscle and nerve cells. Or the comb jellies, which move themselves around by spinning lots of thread-like cilia. Or the truly bizarre placozoans , disk-like creatures that have two sides but no interior and digest things on their surface.

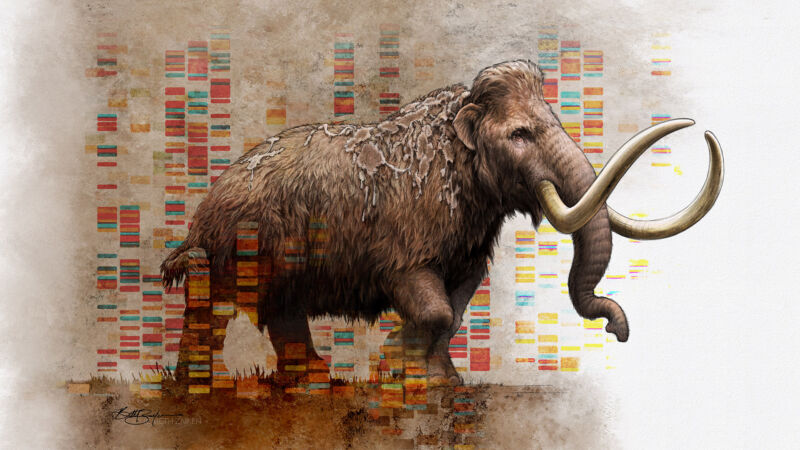

For people who tend to think that evolution involves adding ever-greater complexity to organisms, it's tempting to imagine that the animal family tree came about by progressively adding more stuff, like nerve cells and muscles. But there has been a steady flow of genetic studies that hint that there are two separate lineages that ended up with nerve cells. The results of these studies were a bit dependent upon the genes and species chosen for the analysis. But a new study that's not as dependent upon individual genes now firmly places sponges as more closely related to humans than some other animals with a nervous system.