-

chevron_right

chevron_right

US will see more new battery capacity than natural gas generation in 2023

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Friday, 10 February, 2023 - 19:33 · 1 minute

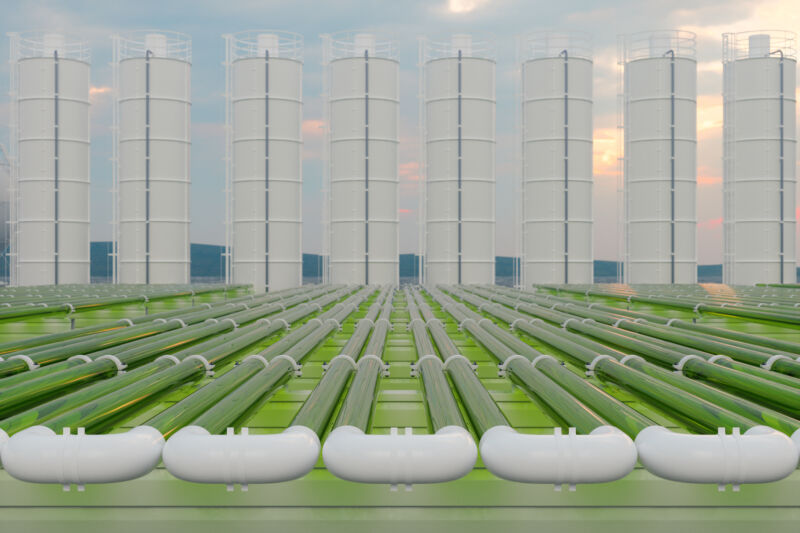

Enlarge / In Texas, solar facilities compete for space with a whole lot of nothing.

Earlier this week, the US' Energy Information Agency (EIA) gave a preview of the changes the nation's electrical grid is likely to see over the coming year. The data is based on information submitted to the Department of Energy by utilities and power plant owners, who are asked to estimate when generating facilities that are planned or under construction will come online. Using that information, the EIA estimates the total new capacity expected to be activated over the coming year.

Obviously, not everything will go as planned, and the capacity estimates represent the production that would result if a plant ran non-stop at full power—something no form of power is able to do. Still, the data tends to indicate what utilities are spending their money on and helps highlight trends in energy economics. And this year, those trends are looking very sunny.

Big changes

Last year , the equivalent report highlighted that solar power would provide nearly half of the 46 Gigawatts of new capacity added to the US grid. This year, the grid will add more power (just under 55 GW), and solar will be over half of it, at 54 percent. In most areas of the country, solar is now the cheapest way to generate power , and the grid additions reflect that. The EIA also indicates that at least some of these are projects that were delayed due to pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions.