-

chevron_right

chevron_right

IBM team builds low-power analog AI processor

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Wednesday, 23 August, 2023 - 19:23

Large Language Models, the AI tech behind things like Chat GPT, are just what their name implies : big. They often have billions of individual computational nodes and huge numbers of connections among them. All of that means lots of trips back and forth to memory and a whole lot of power use to make that happen. And the problem is likely to get worse.

One way to potentially avoid this is to mix memory and processing. Both IBM and Intel have made chips that equip individual neurons with all the memory they need to perform their functions. An alternative is to perform operations in memory , an approach that has been demonstrated with phase-change memory.

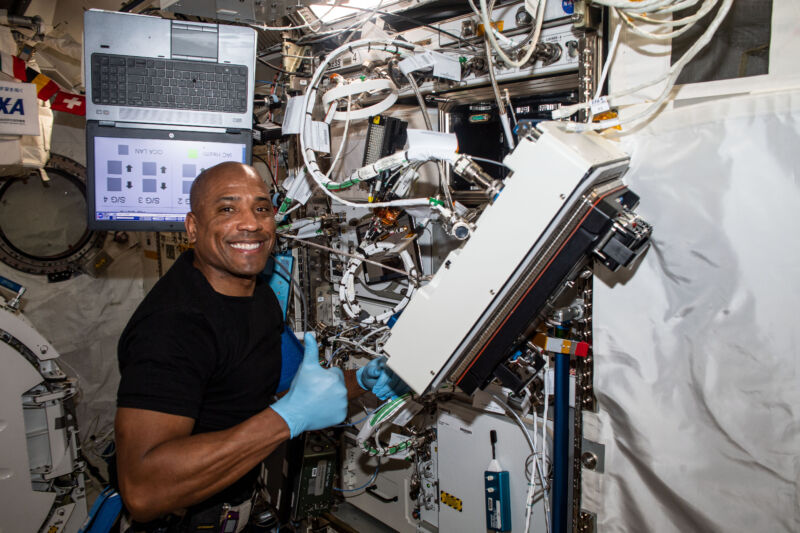

Now, IBM has followed up on its earlier demonstration by building a phase-change chip that's much closer to a functional AI processor. In a paper released on Wednesday by Nature, the company shows that its hardware can perform speech recognition with reasonable accuracy and a much lower energy footprint.