-

chevron_right

chevron_right

NASA launches a billion-dollar Earth science mission Trump tried to cancel

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Thursday, 8 February - 13:37

Enlarge / NASA's PACE spacecraft last year at Goddard Space Flight Center, Maryland. (credit: NASA )

NASA's latest mission dedicated to observing Earth's oceans and atmosphere from space rocketed into orbit from Florida early Thursday on a SpaceX launch vehicle.

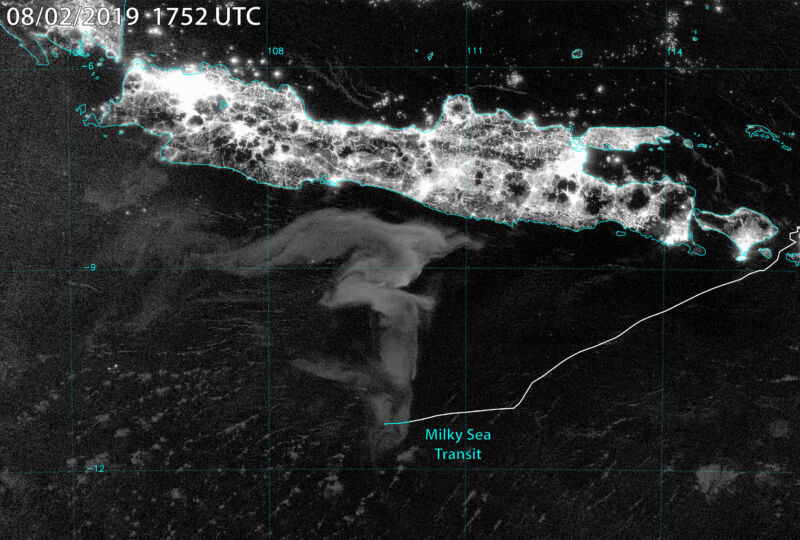

This mission will study phytoplankton, microscopic plants fundamental to the marine food chain, and tiny particles called aerosols that play a key role in cloud formation. These two constituents in the ocean and the atmosphere are important to scientists' understanding of climate change. The mission's acronym, PACE, stands for Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem.

Nestled in the nose cone of a Falcon 9 rocket, the PACE satellite took off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, at 1:33 am EST (06:33 UTC) Thursday after a two-day delay caused by poor weather.