-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Fish’s big mistake preserved an unusual fossil for us

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Wednesday, 20 September, 2023 - 14:57 · 1 minute

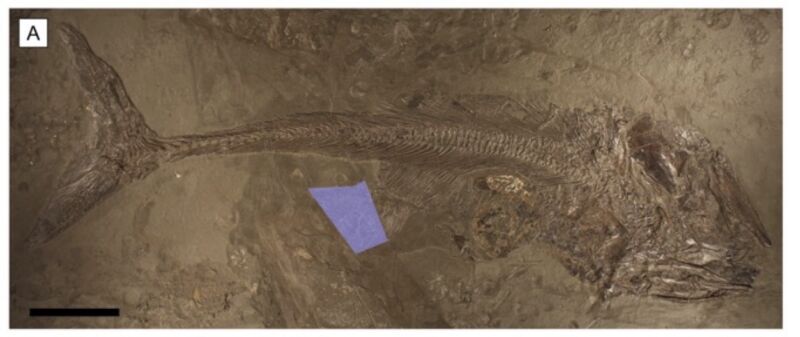

Enlarge / The fish in question, with the ammonite located just below its spine. (credit: Cooper, et. al.)

Some extinct species left copious fossil remnants of their existence. Ammonites —an extinct type of cephalopod—are one such example. From the Devonian through the Paleocene, wherever ancient seas once covered Earth, one can usually find their coiled shells. So one more exquisitely preserved ammonite isn’t necessarily a big deal.

With the exception, perhaps, of one intact example found in the Posidonienschiefer Formation in Germany, where most ammonite shells are flattened and fragmentary. Now, decades after its original discovery, scientists have taken a more careful look at the well-preserved ammonite and the fossil fish it was seemingly nestled against. What they found surprised them: the fish had actually swallowed the large ammonite—something we’ve never seen before, even in fossils of much larger marine species that we know attempted to feed on ammonites.

It didn’t work out well for the fish. The size of the ammonite may have caused the fish to drown, or it may have blocked its digestive tract, causing internal bleeding. Drifting down to the seafloor, the fish was eventually buried and fossilized, preserving that ammonite—along with information about the ecosystem it and the fish inhabited—for over 170 million years.