por

Perla Trevizo

,

Ren Larson

,

Lexi Churchill

,

ProPublica y The Texas Tribune

;

Mike Hixenbaugh

y

Suzy Khimm

,

NBC News

ProPublica es un medio independiente y sin ánimo de lucro que produce periodismo de investigación en pro del interés público.

Suscríbete para recibir sus historias en español por correo electrónico.

Este artículo se publica en conjunto con The Texas Tribune y NBC News. Traducción por Noticias Telemundo.

HOUSTON — Cuando Shalemu Bekele se despertó en la mañana del 15 de febrero, la casa que compartía con su esposa y sus dos hijos estaba tan fría que sentía sus dedos entumecidos.

Luego de abrigarse con más ropa, Bekele miró por una ventana escarchada: una tormenta de invierno había azotado Texas, dejando sin electricidad a millones de hogares, incluido el suyo, y cubriendo Houston con una fina capa de nieve helada.

Never miss the most important reporting from ProPublica’s newsroom. Subscribe to the Big Story newsletter.

“Era hermoso”, recuerda que pensó Bekele, de 51 años, mientras salía para tomarles fotos a sus dos hijos, de 7 y 8 años, jugando por primera vez con la nieve. Después de unos minutos, los hizo entrar a la casa para que se calentaran bajo las cobijas mientras él limpiaba el hielo de su auto, por si tenía que manejar al trabajo.

Never miss the most important reporting from ProPublica’s newsroom. Subscribe to the Big Story newsletter.

Al mismo tiempo, la esposa de Bekele, Etenesh Mersha, de 46 años, tomó una decisión fatídica, repetida por un sinnúmero de residentes de Texas que se quedaron sin electricidad esa semana. Desesperada por calentarse, entró en el garaje y encendió el auto. Con el motor en marcha, podía prender la calefacción del vehículo y cargar su teléfono mientras hablaba con una amiga en Colorado, pero al mismo tiempo, su garaje y su casa se llenaban con un gas venenoso.

La vivienda no tenía una alarma de monóxido de carbono para advertir a la familia del peligro invisible. Ni la ley local o estatal exigían una.

Cuando Bekele regresó a la casa 30 minutos más tarde, encontró a Mersha desplomada en el asiento del conductor, intoxicada por los vapores que salían del tubo de escape del auto. Confundido, la sacudió y la llamó por su nombre. Aún en la línea, la amiga de Colorado suplicaba por el altavoz del auto que alguien le explicara lo que estaba sucediendo.

Sin saber qué más hacer, Bekele, un cristiano devoto, corrió y tomó agua bendita de adentro y se la echó en el rostro a su esposa, mientras sus hijos lloraban y gritaban: “¿Qué le pasa a mamá? ¿Qué está pasando?”.

En ese momento, Mersha vomitó. De repente, él mismo comenzó a sentirse mal, y se preguntó si todos se habrían enfermado con los huevos que había preparado para el desayuno. En pánico, envió a los niños adentro para que trajeran toallas para limpiar a su madre. Antes de que pudieran regresar, ambos niños se derrumbaron dentro de la casa.

Bekele se desmayó a continuación. Su cuerpo cayó, haciendo un ruido sordo al golpear el concreto del garaje, mientras el auto seguía andando.

Luego de que millones de hogares en Texas se quedaron sin luz durante la helada histórica de febrero, familias como la de Bekele enfrentaron una decisión imposible: arriesgarse a la hipotermia o improvisar para mantenerse calientes. Muchos encendieron asadores de carbón dentro de sus casas o pusieron en marcha el motor de sus vehículos en espacios cerrados, sin darse cuenta del peligro o con demasiado frío como para pensar racionalmente.

En su desesperación, miles de texanos, sin saberlo, liberaron gases mortales en casas y apartamentos que, en muchos casos, no estaban equipados con alarmas de monóxido de carbono que pueden salvar vidas. Lo cual resultó en la “mayor epidemia de intoxicación por CO en la historia reciente” del país, según

Neil Hampson

, un médico jubilado que ha pasado más de 30 años investigando la intoxicación por monóxido de carbono y su prevención. Otros dos expertos concuerdan.

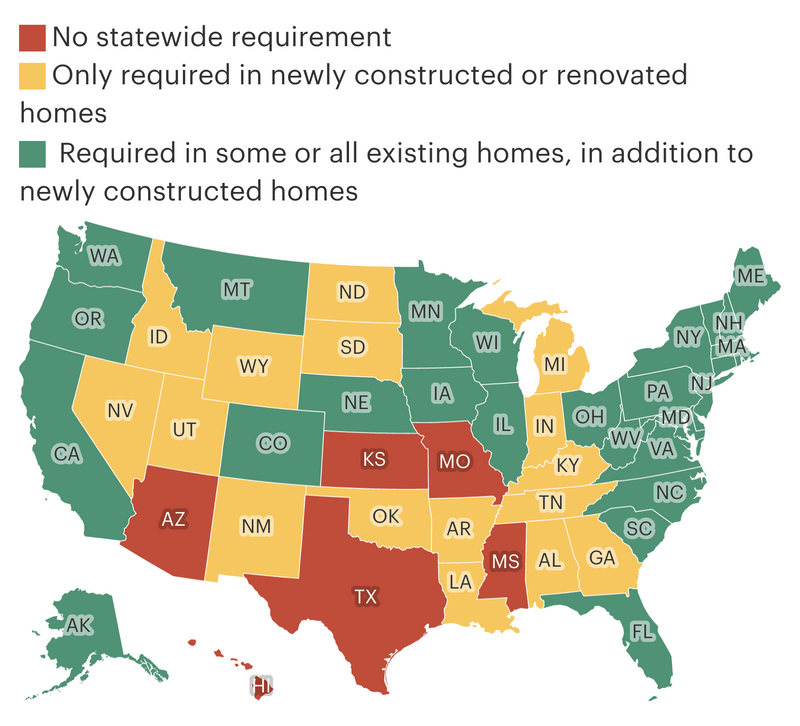

Después de la ola de intoxicaciones sin precedentes de hace dos meses, los legisladores de Texas han tomado pocas medidas para proteger a los residentes de futuras catástrofes relacionadas con el monóxido de carbono. Esa decisión llega a finales de más de una décadade advertencias ignoradas e inacción que han convertido a Texas en uno de los seis estados donde el gobierno estatal no requiere que las viviendas tengan alarmas de monóxido de carbono, según una investigación de ProPublica, The Texas Tribune y NBC News.

Lo que sí tiene Texas es un confuso mosaico de códigos y normas locales, con distintos niveles de protección para los residentes y de cumplimiento limitado, lo que, según expertos en políticas de salud, probablemente contribuye a muertes innecesarias.

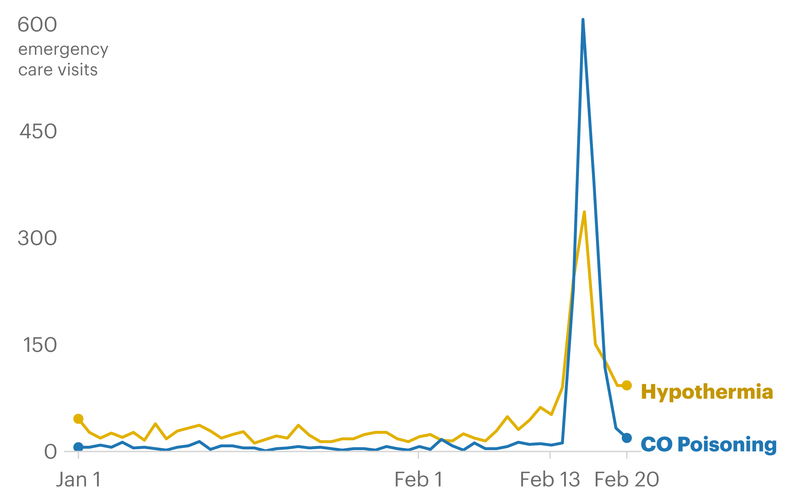

Se ha confirmado que al menos 11 personas murieron y más de 1,400 buscaron atención en salas de emergencia por intoxicación con monóxido de carbono durante el apagón de una semana, solo 400 menos que el total de todo el año 2020. Los niños representaron el 42% de los casos. Estas cifras no incluyen a los residentes que se intoxicaron pero no fueron llevados a un hospital o aquellos que buscaron atención médica en hospitales y clínicas de urgencia que no reportan voluntariamente datos al estado.

Los negros, hispanos y asiáticos sufrieron desproporcionadamente gran parte de las intoxicaciones por monóxido de carbono, según una revisión de datos estatales de hospitales hecha por ProPublica, The Texas Tribune y NBC News. Esos grupos representaron el 72% de las intoxicaciones, mucho más que el 57% que representan en el total de la población del estado.

Durante las últimas dos décadas, la gran mayoría de los estados han implementado leyes o regulaciones que exigen el uso de alarmas de monóxido de carbono en residencias privadas, a menudo después de muertes de alto perfil o intoxicaciones masivas durante tormentas.

Pero en Texas, donde muchos legisladores a menudo ponen la responsabilidad personal por encima de los mandatos estatales, los esfuerzos para aprobar requisitos similares sobre el monóxido de carbono han fracasado una y otra vez.

Los legisladores presentaron una serie de proyectos de ley destinados a renovar la red eléctrica del estado después de la tormenta, cuyo impacto más fuerte se sintió entre el 14 y el 17 de febrero. Las temperaturas bajaron a cifras de un solo dígito, casi 4.5 millones de hogares y negocios de Texas perdieron electricidad en su punto máximo y

más de 150 personas murieron, muchas de ellas congeladas en sus viviendas

.

Las demandas de un cambio provocaron una serie de renuncias pero, con prácticamente todos los medios y legisladores enfocados en las fallas regulatorias que causaron el apagón, poca atención se prestó a las alarmas de monóxido de carbono. Lo cual resultó en la pérdida de una importante oportunidad para “una crisis de salud pública totalmente prevenible”, dijo Emily Benfer, profesora visitante de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Wake Forest en Carolina del Norte, que se especializa en los riesgos de salud en las viviendas.

Este año, los legisladores están considerando una modernización más amplia de los códigos de construcción estatales que no está relacionada con la tormenta de febrero. Si la medida se aprueba, requeriría la instalación de alarmas de monóxido de carbono en algunas casas y apartamentos nuevos, pero no en los construidos antes de 2022. Además, permitiría que los gobiernos locales tengan la oportunidad de optar por no participar.

“Es completamente impactante”, señaló Benfer. “En una sola semana tenemos evidencia concreta del desprecio deliberado de un gobierno estatal por la salud y seguridad de los residentes más vulnerables del estado”.

“Desastre de salud pública”

Bekele y Mersha llegaron a Houston desde Etiopía hace una década con el sueño de una vida mejor para su familia. Durante años, vivieron en un apartamento pequeño y ahorraron de sus sueldos como empleados de gasolineras hasta que pudieron comprar una casa. En 2017, compraron una de tres habitaciones en el suroeste de Houston, donde planeaban ver crecer a su hijo Beimnet y a su hija Rakeb.

Shalemu Bekele con su esposa, Etenesh Mersha, su hija, Rakeb, e hijo, Beimnet.

(Cortesía de la familia Bekele)

Bekele no recuerda si alguien les notificó que la casa no tenía alarmas de monóxido de carbono. La ley estatal requiere que esa información se divulgue cuando se venden viviendas unifamiliares, pero no existe una política en Houston, o en todo Texas, que les exija a los propietarios anteriores instalar una.

“Nunca antes me habían hablado del monóxido de carbono”, dijo Bekele, a través de un intérprete de amárico, su lengua nativa.

Lo primero que recuerda después de desmayarse la mañana del 15 de febrero fue despertar dentro de una ambulancia. Pensó que solo se había desmayado por unos minutos, sin darse cuenta de que ya era pasada la medianoche. Él y su familia habían pasado más de 12 horas inconscientes mientras la amiga de su esposa en Colorado, sin saber su dirección, buscaba frenéticamente en las redes sociales a familiares que pudieran enviar a los socorristas a su hogar.

Bekele comenzó a preguntarles a los paramédicos qué les sucedió a su esposa e hijos, pero antes de que pudiera terminar de pronunciar las palabras volvió a desmayarse.

Finalmente Bekele fue trasladado al Hospital Memorial Hermann en el Centro Médico de Texas, luego de que el conductor tuviera que navegar por caminos cubiertos de hielo. El hospital estaba lleno con pacientes como Bekele. El personal médico estaba atendiendo a tantas personas por intoxicación con monóxido de carbono que se estaban quedando sin camas y tanques de oxígeno, dijo Samuel Prater, director médico del departamento de emergencias.

“Nunca habíamos visto nada como esto”, comentó Prater.

Cada año, el Sistema de Salud Memorial Hermann atiende a unos 50 pacientes por intoxicación con monóxido de carbono en sus 20 salas de emergencia en Houston y los condados alrededor. Pero ese lunes, solo el personal de la sala de emergencias de Prater trató a más de 60. En todo el sistema Memorial Hermann, una de las cadenas de hospitales más grandes de la región de Houston, 224 pacientes buscaron atención médica por intoxicación con monóxido de carbono durante la helada y los cortes de energía, más de cuatro veces de lo que ven en todo un año, según datos facilitados por el hospital.

Rápidamente, Prater consiguió más tanques de oxígeno para la sala de emergencias y estableció protocolos de triaje con el fin de priorizar las limitadas cámaras hiperbáricas del hospital. Las cámaras, que suministran oxígeno a alta presión para eliminar más rápidamente el monóxido de carbono del torrente sanguíneo de los pacientes, son un tratamiento estándar para detener el daño causado por casos graves de intoxicación por CO.

Mientras continuaba la interrupción del suministro eléctrico en millones de hogares de Texas y las temperaturas seguían bajando, Prater les pidió a los encargados de comunicación del Memorial Hermann y la Escuela de Medicina McGovern de UTHealth, donde es profesor, que hablaran con los medios para advertir a los residentes sobre los peligros del monóxido de carbono.

“En términos inequívocos, este es un desastre de salud pública”, dijo Prater en una

conferencia de prensa

televisada un día después, instando a las personas que habían perdido la energía eléctrica a no meter parrillas de carbón o generadores portátiles dentro de sus hogares. “Además, nunca encienda el vehículo dentro de su garaje y luego entre para tratar de calentarse”.

Más tarde en una entrevista, Prater explicó lo que estaba en juego: el monóxido de carbono es un gas incoloro e inodoro que, en altas concentraciones, puede matar en minutos. En casos graves, quienes sobreviven pueden sufrir daño cerebral permanente y otros problemas de salud a largo plazo, como pérdida de memoria, ceguera y daño auditivo.

Casi el 80% de los pacientes tratados esa semana en las instalaciones del Memorial Hermann por intoxicación por monóxido de carbono eran hispanos o negros, aunque esos grupos solo representan el 55% de la población en la región metropolitana de Houston. La mayoría de los pacientes provenían de vecindarios que el hospital identificó como hogar de “poblaciones vulnerables”.

Parte de esta disparidad es el resultado del lugar donde ocurrieron los cortes de energía. En todo el estado, las zonas con una alta proporción de residentes de color tenían cuatro veces más probabilidades de quedarse sin luz en comparación con las áreas predominantemente blancas,

según un análisis

de datos de satélites y del censo de Estados Unidos publicados por la Iniciativa de Crecimiento y Uso de Electricidad en Economías en Desarrollo, una colaboración sin fines de lucro entre cinco universidades.

Cuando se cortó el suministro eléctrico, las familias de las comunidades de bajos ingresos enfrentaron mayores desafíos. Pocos tenían parientes con los que pudieran quedarse. Algunos no tenían vehículos que pudieran manejar en carreteras heladas y otros no tenían conocimiento de los refugios locales a los que podían ir a calentarse. Esto dejó a muchos atrapados en hogares congelados y con un mayor riesgo de intoxicación por monóxido de carbono, dijo Melissa DuPont-Reyes, profesora asistente en Texas A&M que estudia las disparidades en el sistema de salud.

“No tienen otra opción para mantenerse calientes”, dijo. “Van a utilizar todos los medios posibles y, lamentablemente, es tóxico”.

Benfer, la profesora de Wake Forest, concuerda: “Las comunidades más marginadas también están marginadas en el acceso a la información, los recursos y una red de seguridad a la que puedan recurrir en tiempos de crisis”.

Más de 24 horas después de desmayarse, Bekele finalmente recuperó el conocimiento dentro de una de las cámaras hiperbáricas del Memorial Hermann. Inmediatamente preguntó por su esposa e hijos, pero una enfermera le dijo que estaba muy enfermo y necesitaba descansar.

Bekele siguió preguntando, hasta que finalmente una doctora se sentó junto a su cama. Lloró cuando ella le dio la noticia.

Su hijo, Beimnet, estaba conectado a un ventilador en la unidad de cuidados intensivos, le dijo la doctora.

En cuanto a su esposa e hija, la doctora le informó que habían muerto antes de que llegaran los paramédicos, envenenadas por un gas del que, hasta ese momento, Bekele nunca había oído hablar.

Suplicando ayuda

Mientras Bekele se recuperaba en el hospital, las llamadas al 911 siguieron inundando las líneas de emergencia en todo el estado.

En Austin, la capital, Franklin Peña se sentía cada vez más impotente al ver a su hijo de 3 años temblar por el frío brutal que se apoderó de su apartamento. En la noche del 16 de febrero, después de dos días sin electricidad, Peña trajo una parrilla de carbón para quemar leña y calentarse.

“Fue tanta mi desesperación que perdí el miedo o perdí la cabeza”, dijo Peña durante una entrevista. “Lo único que pensé fue meter el asador ”.

Poco después de las 6 pm, la esposa de Peña y sus dos hijos comenzaron a vomitar. Con sus propias piernas temblando, Peña marcó el 911.

“Por favor ayúdenme”, le suplicó a la operadora, según una grabación obtenida a través de una solicitud de información pública. Su esposa lloraba al fondo mientras él le decía a la operadora del 911 que su hijo mayor, de 12 años con discapacidad de desarrollo, se había desmayado. Debido a sus altas tasas metabólicas, dicen los expertos, los niños pueden ser más vulnerables a los efectos del monóxido de carbono.

“¿Están todos fuera de peligro?” preguntó la operadora, mientras Peña explicaba que habían huido de su apartamento y estaban afuera en el frío. “Están respirando pero no están bien”, respondió.

Durante 30 intensos minutos, el mexicano de 37 años trató de responder las preguntas de la operadora mientras su esposa y su hijo seguían desmayándose una y otra vez. “

Please

, saca fuerzas, mami”, repetía entre sollozos, suplicando a su esposa que resistiera.

Un informe posterior del incidente citó “niveles extremos” de monóxido de carbono en el apartamento de la familia, que según Peña no tenía alarmas para detectar este gas.

No eran requeridas.

Texas le ha dado a los gobiernos locales la discreción de establecer sus propias reglas sobre el monóxido de carbono. Como resultado, los requisitos varían ampliamente y ninguna agencia los rastrea en todo el estado.

Fort Worth y Dallas requieren los dispositivos en viviendas construidas recientemente y en unidades multifamiliares existentes, pero no en la mayoría de las viviendas unifamiliares. Houston solo los exige para las casas nuevas o remodeladas, aunque actualmente está considerando un requisito más amplio que incluirá viviendas ya construidas. La mayoría de las comunidades rurales tienen aún menos supervisión.

Incluso en ciudades con regulaciones más estrictas, muchos hogares carecen de los dispositivos.

En 2017, Austin votó para convertirse en la primera ciudad principal de Texas en requerir alarmas de monóxido de carbono en muchas residencias nuevas y existentes en donde hay electrodomésticos que queman combustible o garajes adjuntos a la casa. El cambio se debió, en parte, a un incidente que ocurrió años antes en donde dos residentes murieron.

La casa de Peña solo tenía electrodomésticos, lo que excluía su apartamento del requisito.

Cuando los socorristas finalmente llegaron a la casa de Peña, lo llevaron a él, a su esposa y a su hijo de 12 años al hospital por intoxicación con monóxido de carbono. A su niño de 3 años se le suministró oxígeno pero no se le transportó al hospital. Peña, quien trabaja pintando y remodelando casas, dijo que todos se han recuperado desde entonces, pero ocasionalmente sufren dolores de cabeza y el trauma de lo que vivieron esa noche.

“Si nosotros vemos que está haciendo frío, sentimos temor”, dijo. “Si vemos que algo hace humo en la estufa, sentimos temor, y nos regresa todo lo que pasamos”.

Los datos estatales de las salas de emergencias no reflejan la cantidad de residentes por ciudad o condado que visitaron hospitales por intoxicación con monóxido de carbono. Pero los registros de llamadas al 911 obtenidos y analizados por ProPublica, The Texas Tribune y NBC News muestran que, en Austin y los alrededores del condado de Travis, la mayoría de las 60 llamadas de emergencia por monóxido de carbono provienen de vecindarios vulnerables, donde los residentes tienen ingresos que equivalen a dos tercios del promedio en el condado de Travis.

Las vulnerabilidades fueron más graves alrededor de Rundberg Lane en el norte de Austin, donde vive Peña. Un tercio de las llamadas de emergencia por monóxido de carbono de la ciudad provinieron de esta comunidad, con más del doble de la proporción de inmigrantes y refugiados del condado. Aproximadamente 4 de cada 5 residentes en el área son personas de color y casi 2 de cada 5 no dominan el inglés, según un análisis de las llamadas al 911 y los datos del censo de Estados Unidos realizado por los medios que realizaron esta investigación.

A tres millas de la casa de Peña, la familia de Lucila Montoya metió una estufa portátil de gas dentro de la casa para cocinar el almuerzo y un asador con carbón encendido para ayudar a calentar la vivienda. No sabían que las brasas siguen emitiendo gases tóxicos, incluso después de que las llamas se apagan.

A la hora, Montoya se empezó a sentir débil pero pensó que era su embarazo. Estaba programada para dar a luz en marzo. Pero luego su hija Tifany, de 7 años, comenzó a llorar y a perder el conocimiento. Montoya tomó el teléfono mientras su esposo, José, se puso a la niña sobre su espalda y la sacó en medio de la tormenta.

“Mi niña se puso mal, empezó a vomitar y mi niña no responde, por favor”, dijo Montoya entre llanto a la operadora del 911 a través de una intérprete en español. “Necesito que vengan rápido... ella apenas respira”.

La madre de 28 años, nativa de Honduras, estuvo hospitalizada un día junto con su hija. Recordó a Tifany diciendo que no podía respirar. “Sentía que iba a morir”, dijo Montoya, cuya casa tampoco tenía alarma de monóxido de carbono.

“Inocentes nosotros, íbamos a acabar con la vida de ella y de paso la mía”, agregó Montoya, quien el mes pasado dio a luz a una niña sana. “Como madre, no le deseo esto a nadie”.

Intentos fallidos de reforma

En las semanas y meses posteriores a los cortes de electricidad, los legisladores de Texas se apresuraron para presentar y aprobar proyectos de ley destinados a renovar la red eléctrica del estado, con el objetivo de prevenir futuros desastres.

“Cuando veo personas que mueren de hipotermia o intoxicación por monóxido de carbono, cuando veo interrupciones en la comunidad empresarial, personas que no pueden conseguir comida caliente, que no pueden conseguir agua... esto no se puede tolerar”,

declaró en febrero

el vicegobernador de Texas

Dan Patrick

, un republicano que establece las prioridades legislativas en el Senado estatal.

Pero mientras los legisladores exigían una ola de reformas complejas, hicieron poco para abordar uno de los cambios más simples: establecer un requisito estatal para las alarmas de monóxido de carbono en los hogares.

Los tres principales republicanos del estado —

el gobernador Greg Abbott, el presidente de la Cámara de Representantes, Dade Phelan

, y Patrick— no respondieron a preguntas sobre por qué la seguridad ante el monóxido de carbono no era una prioridad legislativa.

La representante estatal Donna Howard

, una demócrata de Austin y miembro del comité legislativo donde se discutieron las reformas energéticas, dijo que el monóxido de carbono no estaba en su radar. Pero admitió que debería de haberlo estado basado en los hallazgos de ProPublica, The Texas Tribune y NBC News.

“Claramente, a lo largo de esta discusión se nos tuvo que recordar sobre el hecho de que hubo gente que murió”, dijo. “Todos sabemos lo trágico que es, pero nos vemos atrapados en la política, y a veces perdemos de vista el resultado final”.

En Texas, propuestas legislativas que buscan crear regulaciones estatales para las alarmas de monóxido de carbono han fallado repetidamente, incluso después de grandes tormentas que provocaron un aumento en las intoxicaciones y muertes por CO. Un proyecto de ley presentado en 2019 que habría exigido los dispositivos en viviendas de alquiler no obtuvo una audiencia.

La exsenadora estatal Leticia Van de Putte, una demócrata de San Antonio, fue coautora de una medida fallida en 2007, un año después de que el exsenador estatal Frank Madla y su suegra murieran en un incendio en su casa. Su nieta de 5 años, que también estaba en la casa, murió por intoxicación con monóxido de carbono.

La medida habría requerido detectores de humo y alarmas de monóxido de carbono en las nuevas construcciones y casas antiguas a la venta, si las residencias tenían electrodomésticos que usaran combustible.

Pero el proyecto de ley no avanzó a pesar de la estrecha conexión que muchos legisladores tenían con Madla y el testimonio de apoyo de jefes de bomberos, un médico de la sala de emergencias y un representante del centro de control de intoxicaciones.

Grupos de la industria —como la Asociación de Constructores de Texas— se opusieron firmemente en ese momento,

criticando

las alarmas de monóxido de carbono como una “tecnología no probada” que haría más daño que bien, si se exigía su implementación.

“Creemos que exigir esto crearía una falsa sensación de seguridad para los propietarios y abriría la responsabilidad de los constructores en caso de que fallen”, dijo en 2007 Ned Muñoz, vicepresidente de asuntos regulatorios y asesor general del grupo, durante una audiencia en la Cámara de Representantes. Muñoz también señaló que los dispositivos aún no estaban incluidos en los códigos de construcción internacionales que son ampliamente adoptados por los gobiernos estatales y locales.

Para Van de Putte no queda duda de que el hecho de que el estado no haya aprobado una política sobre el monóxido de carbono costó vidas en febrero.

“Tenemos tantas cosas que protegen lo físico, lo tangible, la propiedad”, dijo Van de Putte, una farmacéutica, sobre las regulaciones actuales. “Al no poner alarmas de monóxido de carbono, eso es lo que estamos valorando. Estamos valorando la propiedad por encima de la vida”.

Desde el fracaso del proyecto de ley de 2007, las alarmas de monóxido de carbono

se han vuelto más confiables

y ahora son requeridas por la mayoría de los gobiernos estatales y

recomendadas

por las principales organizaciones de salud y seguridad. El Consejo Internacional de Códigos

las recomendó por primera vez

en 2009 para nuevas construcciones y viviendas unifamiliares remodeladas, y para complejos de apartamentos en 2012.

A raíz de los nuevos estándares, la Asociación de Constructores de Texas ha cambiado su posición, dijo Scott Norman, director ejecutivo del grupo. Ahora, la organización apoya los requisitos para las alarmas de monóxido de carbono en las residencias recién construidas o remodeladas, señaló Norman.

“Hace décadas, había dudas sobre la confiabilidad”, dijo. “Pero los códigos evolucionan”.

Los defensores de la seguridad contra incendios y los expertos en salud pública dicen que un requisito estatal de alarmas de monóxido de carbono protegería mejor a los residentes y ayudaría a transmitir el mensaje sobre el peligro mortal.

“No sabes si vas a estar expuesto hasta que es demasiado tarde y estás enfermo o muerto”, dijo John Riddle, presidente de la Asociación de Bomberos del Estado de Texas, que representa a los socorristas. “Una ley o requisito a nivel estatal facilitaría mucho las cosas”.

En algunos de los estados que han aprobado reglas sólidas ha habido una reducción significativa de las intoxicaciones, según los expertos en seguridad contra incendios.

“Cuando el estado llega y lo exige, hay continuidad en todo el territorio: hay un mensaje”, dijo Jim Smith, jefe de bomberos del estado en Minnesota, donde las visitas al departamento de emergencias por intoxicación con monóxido de carbono disminuyeron en un 45%, de 411 a 226, en los siete años posteriores a que ese estado aprobara una ley general que requería alarmas en la mayoría de las residencias privadas. “No es diferente a un cinturón de seguridad”.

A principios de abril, la Cámara de Representantes de Texas

aprobó un proyecto de ley

que requeriría que las ciudades se adhirieran a los códigos de salud y seguridad más recientes para las residencias recién construidas y remodeladas. Según la medida, aún no aprobada por el Senado estatal, se requerirán alarmas de monóxido de carbono en las casas construidas después de 2022 que tengan electrodomésticos que funcionen con combustible o garajes adjuntos. El requisito no se aplicaría en zonas no incorporadas a menos que los condados decidan adoptar los códigos, y las ciudades pueden optar por no participar.

La legislación, tal como está redactada, no protegería a millones de texanos que viven en casas y apartamentos ya construidos.

Volver a empezar

En Houston, luego de pasar cuatro días en el hospital, Bekele estaba lo suficientemente bien como para ser dado de alta, pero no regresó a su casa. Durante días, se mantuvo al lado de la cama de su hijo, saliendo solo para ducharse en la casa de un familiar, mientras una máquina bombeaba oxígeno dentro y fuera de los pulmones del niño.

Bekele estuvo allí, al lado de Beimnet, unos días después, para conmemorar su noveno cumpleaños.

Inicialmente, los médicos le dijeron que su hijo tenía “una probabilidad muy baja de sobrevivir”, dijo Bekele. Incluso si lo hiciera, advirtieron que probablemente sufriría daño cerebral permanente. La exposición prolongada al monóxido de carbono había impedido que el oxígeno llegara a su cerebro.

Día tras día, Bekele tomaba la mano de su hijo y le rogaba a Dios que lo salvara.

A casi dos semanas de ser hospitalizado, Beimnet recuperó el conocimiento. En cuestión de días, dejó de recibir soporte vital y se levantó y comenzó a caminar por el hospital, fortaleciéndose lentamente hasta que estuvo lo suficientemente bien para ser dado de alta.

Dos meses después del accidente, Beimnet toma pastillas para prevenir una recaída con convulsiones como las que sufrió por su exposición al monóxido de carbono pero, por lo demás, hasta el momento, no muestra signos de daño permanente.

“Ahora asiste a la escuela y le va bien”, dijo Bekele, quien desde entonces regresó a trabajar en la gasolinera.

Bekele y Beimnet en abril.

(Annie Mulligan para ProPublica/The Texas Tribune/NBC News)

Este mes, Bekele demandó a casi una docena de empresas que suministran energía a la red eléctrica del estado, una de las decenas de demandas que buscan responsabilizar a las empresas de Texas por lesiones graves y muertes causadas durante los cortes de energía del invierno. Las compañías eléctricas aún no han presentado una respuesta a la demanda de Bekele en el Tribunal de Distrito del condado de Harris, pero en casos similares presentados en otras partes de Texas, niegan su responsabilidad por muertes relacionadas con los apagones.

Bekele no sabe qué pasará con el caso, pero dijo que ninguna cantidad de dinero puede compensar lo que perdió.

Todavía no ha tenido fuerzas para regresar al lugar que él y su familia llamaban hogar antes de que muriera su esposa y su hija. Con la esperanza de un nuevo comienzo, tomó el dinero recaudado por sus seres queridos en GoFundMe y lo destinó al depósito de seguridad y al alquiler de un apartamento cercano. Es más pequeño que su antigua casa en la ciudad, pero con suficiente espacio para los dos.

No mucho después de mudarse, Bekele descubrió un problema, uno que planea solucionar lo antes posible: el apartamento no tiene alarmas de monóxido de carbono.

Acerca de los datos

: Los datos de las salas de emergencias estatales son del 13 al 20 de febrero y provienen del Texas Syndromic Surveillance System. Los pacientes informaron voluntariamente sobre su raza y etnia. Se eliminó del análisis un total de 11% de las personas que no informaron sobre su raza o etnia. Otro análisis sobre la edad de los pacientes eliminó menos del 5% de las personas cuya edad faltaba. Los datos económicos y demográficos provienen de la Encuesta de la Comunidad Estadounidense realizada durante cinco años y publicada en 2019 y se analizaron a nivel de tramo censal. A menos de que se indique lo contrario, las áreas con llamadas de EMS se compararon con toda el área de servicio de EMS de la ciudad de Austin y el condado de Travis.

chevron_right

chevron_right

Snow surrounds an Austin Energy station in Austin, Texas, on Thursday, Feb. 18, 2021. Many Texas residents are still without power and working water.

Sergio Flores for The Texas Tribune

Snow surrounds an Austin Energy station in Austin, Texas, on Thursday, Feb. 18, 2021. Many Texas residents are still without power and working water.

Sergio Flores for The Texas Tribune

The Blanco Vista neighborhood of San Marcos was blanketed with several inches of snow Feb. 15 after a massive winter weather system engulfed Texas, causing widespread power outages across the state.

Jordan Vonderhaar for The Texas Tribune

The Blanco Vista neighborhood of San Marcos was blanketed with several inches of snow Feb. 15 after a massive winter weather system engulfed Texas, causing widespread power outages across the state.

Jordan Vonderhaar for The Texas Tribune

A car moved Thursday through a West Austin neighborhood that was without power.

Jordan Vonderhaar for The Texas Tribune

A car moved Thursday through a West Austin neighborhood that was without power.

Jordan Vonderhaar for The Texas Tribune

Jacob Duran warmed his hands over a grill Thursday after his apartment lost power due to the severe winter storm that hit Texas.

Miguel Gutierrez Jr./The Texas Tribune

Jacob Duran warmed his hands over a grill Thursday after his apartment lost power due to the severe winter storm that hit Texas.

Miguel Gutierrez Jr./The Texas Tribune