Enlarge

/

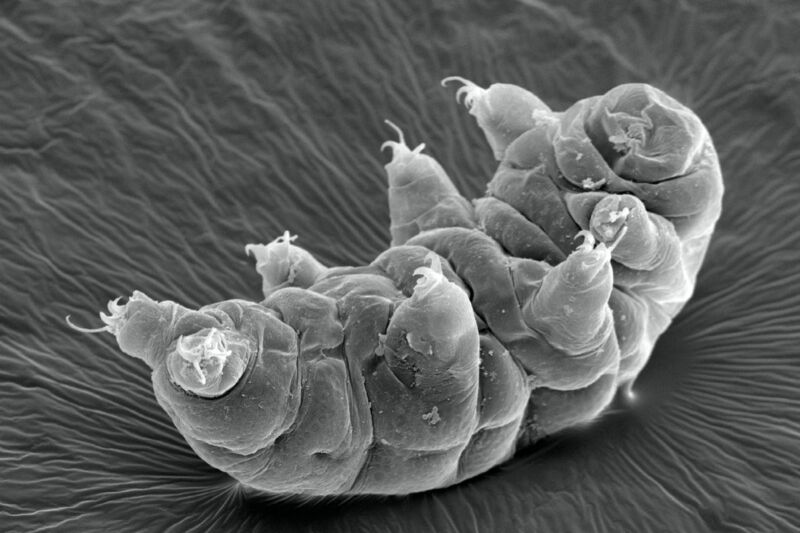

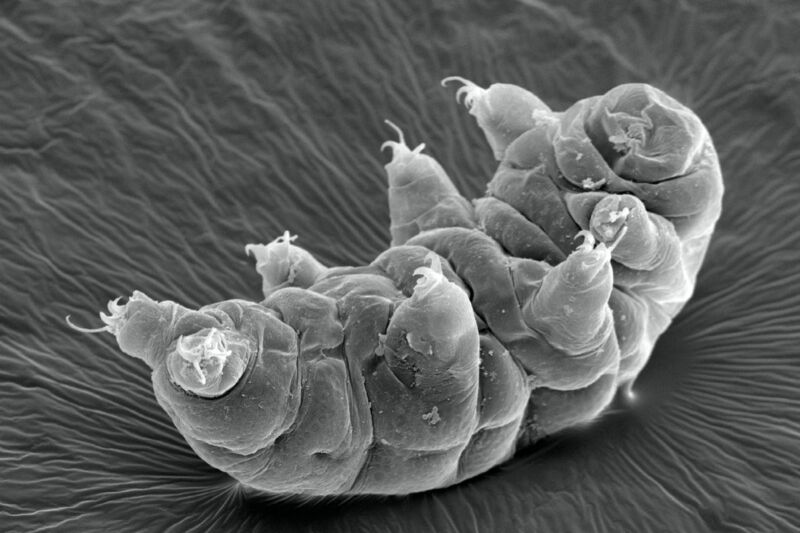

SEM Micrograph of a tardigrade, more commonly known as a "water bear" or "moss piglet." (credit: Cultura RM Exclusive/Gregory S. Paulson/Getty Images)

Since the 1960s, scientists have known that the tiny tardigrade can withstand very intense radiation blasts 1,000 times stronger than what most other animals could endure. According to a

new paper

published in the journal Current Biology, it's not that such ionizing radiation doesn't damage tardigrades' DNA; rather, the tardigrades are able to rapidly repair any such damage. The findings complement those of a

separate study

published in January that also explored tardigrades' response to radiation.

“These animals are mounting an incredible response to radiation, and that seems to be a secret to their extreme survival abilities,”

said co-author Courtney Clark-Hachtel

, who was a postdoc in Bob Goldstein's lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which has been conducting research into tardigrades for 25 years. “What we are learning about how tardigrades overcome radiation stress can lead to new ideas about how we might try to protect other animals and microorganisms from damaging radiation.”

As

reported previously

, tardigrades are micro-animals that can survive in the harshest conditions: extreme pressure, extreme temperature, radiation, dehydration, starvation—even exposure to the vacuum of outer space. The creatures were first described by German zoologist Johann Goeze in 1773. They were dubbed

tardigrada

("slow steppers" or "slow walkers") four years later by Lazzaro Spallanzani, an Italian biologist. That's because tardigrades tend to lumber along like a bear. Since they can survive almost anywhere, they can be found in lots of places: deep-sea trenches, salt and freshwater sediments, tropical rain forests, the Antarctic, mud volcanoes, sand dunes, beaches, and lichen and moss. (Another name for them is "moss piglets.")

chevron_right