-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Is distributed computing dying, or just fading into the backdrop?

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Tuesday, 11 July, 2023 - 13:44 · 1 minute

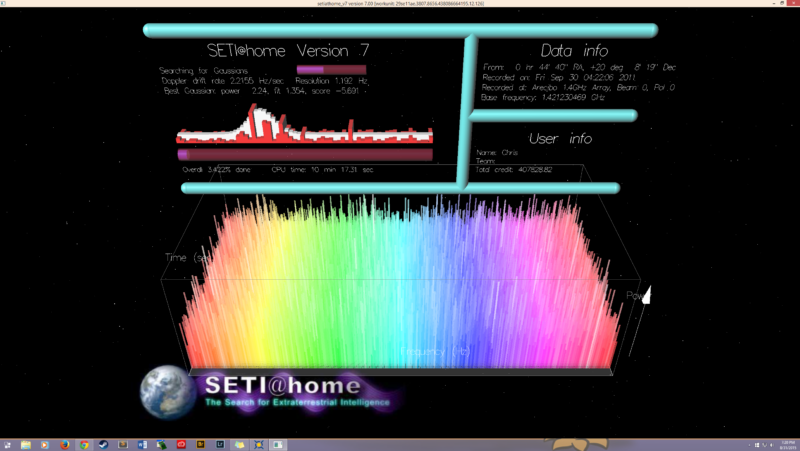

Enlarge / This image has a warm, nostalgic feel for many of us. (credit: SETI Institute )

Distributed computing erupted onto the scene in 1999 with the release of SETI@home, a nifty program and screensaver (back when people still used those) that sifted through radio telescope signals for signs of alien life.

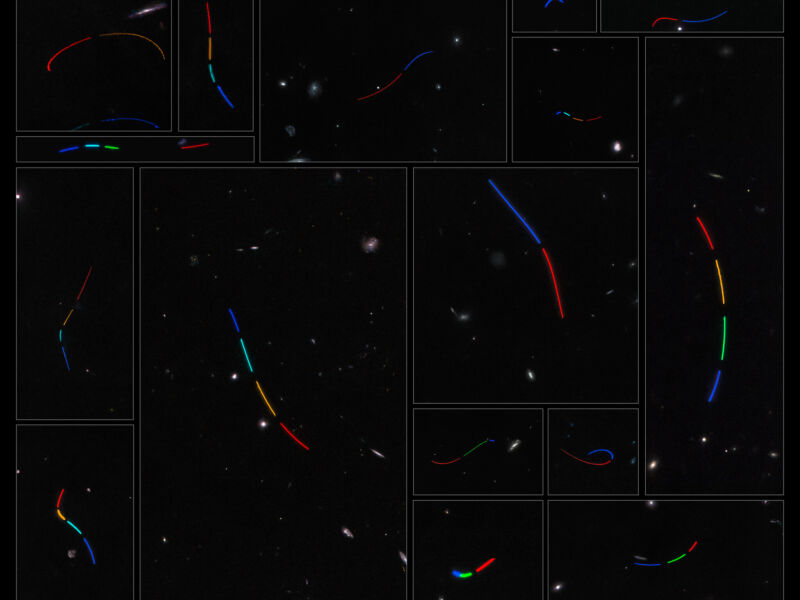

The concept of distributed computing is simple enough: You take a very large project, slice it up into pieces, and send out individual pieces to PCs for processing. There is no inter-PC connection or communication; it’s all done through a central server. Each piece of the project is independent of the others; a distributed computing project wouldn't work if a process needed the results of a prior process to continue. SETI@home was a prime candidate for distributed computing: Each individual work unit was a unique moment in time and space as seen by a radio telescope.

Twenty-one years later, SETI@home shut down, having found nothing. An incalculable amount of PC cycles and electricity wasted for nothing. We have no way of knowing all the reasons people quit (feel free to tell us in the comments section), but having nothing to show for it is a pretty good reason.