-

chevron_right

chevron_right

US’s power grid continues to lower emissions—everything else, not so much

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Friday, 26 April - 18:51

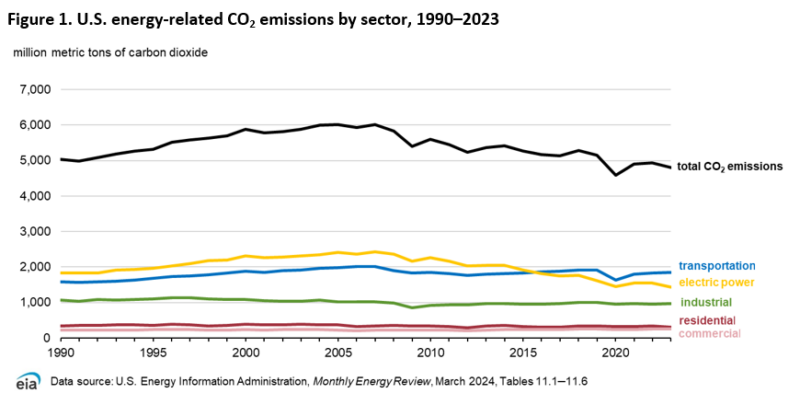

On Thursday, the US Department of Energy released its preliminary estimate for the nation's carbon emissions in the previous year. Any drop in emissions puts us on a path that would avoid some of the catastrophic warming scenarios that were still on the table at the turn of the century. But if we're to have a chance of meeting the Paris Agreement goal of keeping the planet from warming beyond 2° C, we'll need to see emissions drop dramatically in the near future.

So, how is the US doing? Emissions continue to trend downward, but there's no sign the drop has accelerated. And most of the drop has come from a single sector: changes in the power grid.

Off the grid, on the road

US carbon emissions have been trending downward since roughly 2007, when they peaked at about six gigatonnes. In recent years, the pandemic produced a dramatic drop in emissions in 2020, lowering them to under five gigatonnes for the first time since before 1990, when the EIA's data started. Carbon dioxide release went up a bit afterward, with 2023 marking the first post-pandemic decline, with emissions again clearly below five gigatonnes.