ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

-

Pr

chevron_right

“No Good Choices”: HHS Is Cutting Safety Corners to Move Migrant Kids Out of Overcrowded Facilities

pubsub.do.nohost.me / ProPublica · Thursday, 1 April, 2021 - 12:00 · 9 minutes

The startling images have appeared in one news report after another: children packed into overcrowded, unsafe Border Patrol facilities because there was nowhere else to put them. As of March 30, over 5,000 children were being held in Border Patrol custody, including more than 600 in each of two units in Donna, Texas, that were supposed to hold no more than 32 apiece under COVID-19 protocols.

But as the Biden administration’s Department of Health and Human Services scrambles to open “emergency” temporary facilities at military bases, work camps and convention centers to house up to 15,000 additional children, it’s cutting corners on health and safety standards, which raises new concerns about its ability to protect children, according to congressional sources and legal observers. And even its permanent shelter network includes some facilities whose grants were renewed this year despite a record of complaints about the physical or sexual abuse of children.

“There may be no good choices,” Mark Greenberg, a former head of the Administration for Children and Families (which oversees the unaccompanied-children program) at the HHS, told ProPublica. “Everything has to be weighed against the alternative. And the alternative is the backups at Customs and Border Protection. And recognizing how bad that is, it means that people have to make unpalatable decisions.”

According to internal government statistics and interviews with former officials, legal observers, advocates and congressional staff, those decisions came weeks or months after the first warning signs late last year that the number of unaccompanied minors crossing the southern U.S. border was rapidly increasing, forcing a scramble to set up facilities in a matter of days. No safety standards are in place at the new facilities — unlike controversial “influx” facilities used in the past.

One new site in Midland, Texas, was briefly closed to new arrivals after the state warned that its water wasn’t drinkable . That site and others have been staffed with volunteers who may not have passed background checks and speak no Spanish. One potential site — a NASA research center in Moffett, California — was scuttled after local protesters pointed out it was near a known Superfund site with high levels of toxic chemicals.

While previous influx sites have been criticized by Democrats in Congress and immigration advocates for sometimes falling short of state standards for licensed facilities, HHS has generally agreed to hold operators to those standards, said attorney Leecia Welch of the National Center for Youth Law. But it hasn’t committed to that now. Nor has HHS offered any other standards it plans to hold the facilities to. In a statement provided to ProPublica, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said, “We are seeing progress, but it takes time. In the meantime, the CBP workforce has done heroic work under difficult circumstances to protect these children.” HHS did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s “the Wild West,” Welch said, reflecting a view shared by other advocates and congressional staff monitoring the children’s care.

Meanwhile, the federal government has tried to revive its COVID-19-battered network of permanent residential facilities. In January, it quietly renewed three-year grants to several state-licensed providers that previously faced complaints of physical or sexual abuse of children. The facilities have defended their care without denying the allegations.

One grant went to a Texas facility that children were removed from in 2018 amid allegations that staffers were d rugging them , and that had previously fired a staff member for placing a child in a chokehold in 2019. Two organizations that have faced repeated allegations of sexual abuse also had their grants renewed: a foster-care provider in New York accused of placing children with abusers, and a shelter in Pennsylvania where children accused the staff of abuse. The New York organization told ProPublica, “The safety of the youth in our care is of the utmost importance to us and has always been,” and it stressed that both staff and potential fosterers go through “extensive background checks.” Neither of the other facilities responded to requests for comment.

By federal law, children are to be held no longer than 72 hours in Border Patrol custody before they are transferred to HHS housing, except in emergency situations. As of March 30, however, over 2,000 children being held at the main Border Patrol facility in Donna had been there for more than 72 hours, according to reporters.

In recent years, Border Patrol facilities for children have l acked toothbrushes or medical supplies , and the fact that Border Patrol agents aren’t trained to deal with children raises risks that a child will become ill or even die in U.S. custody. This has convinced many officials working in the system that deals with unaccompanied migrant children (including some within Customs and Border Protection) that releasing kids into any HHS care is better than leaving them in Border Patrol custody.

HHS normally places children in a network of shelters while their relatives in the U.S. are identified and vetted (a process that, during the pandemic, has typically taken at least a month). When needed, HHS has also opened influx centers that can be set up in weeks and do not require state licensing. Now, with the assistance of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, HHS is opening new “emergency intake sites” in a matter of days, including two in convention centers in Dallas and San Diego.

HHS also relies on a network of state-licensed shelters, which are required to self-report violations found by state regulators to the federal government. A 2020 Government Accountability Office report found that HHS offered unclear instructions on how such violations should be reported. One grantee, which was cited by state auditors 70 times in two years for violations at three facilities, mentioned none of those violations in its reports to HHS.

Shelters operated by the advocacy organization Texas Impact, an HHS contractor, were cited for 68 violations involving physical abuse or unnecessary restraint of a child. In two cases, children were placed in chokeholds by staff members attempting to restrain them. (In both cases, the staffers responsible were fired.)

In an incident at a shelter near Houston in 2019, a child reported being held in a chokehold for over two minutes. The facility operator (initially operating under the name Daystar Residential Centers) closed in 2011 after a string of abuse allegations, only to reform under the name Shiloh Treatment Centers a few years later. In 2018, the facility was accused in a legal filing of sedating children with antipsychotic drugs . In response, a federal judge ordered the removal of all children who weren’t considered at risk of harming themselves or others. (The shelter did not respond to a ProPublica request for comment.)

Shiloh was among the 23 facilities awarded new three-year contracts on Jan. 1, receiving two grants totalling $2.6 million. The facility has held only a few children during the pandemic, and Welch said it’s possible that conditions have improved. At her last monitoring visit, she said, she heard none of the horror stories that children had told her in the past. But as the GAO report noted, HHS doesn’t explicitly look at past performance when evaluating grant renewals.

The HHS housing crunch has been badly exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. Children’s shelters, like other kinds of congregate housing, are under severe capacity restrictions that reduce available bed space.

The HHS shelter population was growing last fall, even before a federal judge ruled in November that the Trump administration had to take unaccompanied migrant children in, rather than expelling most of them from the U.S. immediately under a March public-health order issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. From Oct. 31 to Nov. 30, the number of children in HHS custody rose from about 2,000 to about 3,000. In mid-December, with about 3,500 kids in custody, HHS officials said in a briefing that shelters near the U.S.-Mexico border were already at 67% of their capacity limits under COVID-19. But HHS took no action to add capacity until Jan. 15, when it sent a message to other government agencies asking them to scout locations for potential influx sites.

Former DHS officials said that HHS has long resisted taking emergency measures, straining the agency’s relationship with Border Patrol. During a similar crunch in 2019, one former DHS official told ProPublica that HHS “refused to acknowledge the operational challenges” that were leading children to be marooned in Border Patrol custody for days, out of a belief that “immigration was kind of a third rail.”

“It’s no coincidence that in each of the surges since 2014, FEMA — the emergency-management arm of DHS — has had to step in,” another former DHS official said. “When the [HHS] system is overwhelmed by the number of intakes, they don’t have the FEMA-like capacity to think improvisationally, to rush resources, or to modify processes, and they become the bottleneck.”

On March 5, the CDC waived the COVID-19 capacity caps for migrant child shelters so HHS could take more children out of Border Patrol facilities. The Biden administration is now working with states to allow shelters to house more children while complying with state licensing requirements. But shelters are struggling to hire staff, as many qualified professionals still fear working in congregate housing because new coronavirus variants are spreading. HHS recently informed Congress that it has upped its incentive pay to help recruiting, but it’s unclear if that will be enough.

A senior administration official acknowledged in March that the number of beds being made available would at best be a few hundred a week — far too few compared to the number of children arriving.

When the Biden administration announced it was reopening the influx care facility in Carrizo Springs, Texas, in February, immigration advocates and some Democrats condemned it as another way to keep “kids in cages.” Meanwhile, the other influx facility opened by the Trump administration in 2019, at Homestead Air Reserve Base in Miami, was held in reserve. At present, it appears it won’t be reopened; Axios reported that Biden himself stepped in to veto the possibility.

But HHS policy requires influx facilities to “comply, to the greatest extent possible, with State child welfare laws and regulations (such as mandatory reporting of abuse), as well as State and local building, fire, health and safety code.” There are no such commitments in place for emergency facilities, according to Welch and congressional staff. It’s still not clear who will operate the facilities after the initial setup is completed, or whether HHS will require them to provide support services to children, such as mental health counseling or legal assistance.

People who work in the system often point out that the ultimate goal is to get children reunited with their U.S.-based relatives as quickly and safely as possible. The lack of support services might matter less if children did not end up staying at the new emergency sites for months, they argue.

“We would always want children in a good, safe, developmentally appropriate setting,” Greenberg told ProPublica. “But the issue is just really different for a child who is going to be somewhere for 30 days” compared to longer-term stays.

Ultimately, how long emergency sites remain open depends on how long children keep coming to the U.S. in numbers beyond what HHS can accommodate. Internal government estimates obtained by The Wall Street Journal predict that as many as 25,000 children could cross into the U.S. in May.

A child’s shoe lies abandoned near an illegal river-crossing point at the U.S.-Mexico border on March 24, 2021, in McAllen, Texas.

(John Moore/Getty Images)

A child’s shoe lies abandoned near an illegal river-crossing point at the U.S.-Mexico border on March 24, 2021, in McAllen, Texas.

(John Moore/Getty Images)

The closed-down migrant camp in Matamoros, Mexico, on Feb. 24.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

The closed-down migrant camp in Matamoros, Mexico, on Feb. 24.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Asylum seekers make their way across the Gateway International Bridge in Matamoros, Mexico, on Feb. 26, to be processed in the U.S. Some had been living at the Matamoros migrant camp for nearly two years after being sent back to Mexico under the Migrant Protection Protocols to wait for their cases to be decided.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Asylum seekers make their way across the Gateway International Bridge in Matamoros, Mexico, on Feb. 26, to be processed in the U.S. Some had been living at the Matamoros migrant camp for nearly two years after being sent back to Mexico under the Migrant Protection Protocols to wait for their cases to be decided.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Salvadoran asylum seeker Vilma Vasquez lived for nearly two years in a tent at a migrant camp in Matamoros, Mexico. In November 2019, her daughter, then 15, crossed the border as an unaccompanied minor after constantly feeling sick at the encampment.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Salvadoran asylum seeker Vilma Vasquez lived for nearly two years in a tent at a migrant camp in Matamoros, Mexico. In November 2019, her daughter, then 15, crossed the border as an unaccompanied minor after constantly feeling sick at the encampment.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

At a bus station in Brownsville, Texas, Guatemalan asylum seeker Jorge Mario Gonzalez shows scars from a surgery he had after being shot in his country. Gonzalez said he was shot near the ribs and the bullet went through his body, affecting a nerve, leaving him needing crutches to walk. He and his wife were sent back to Mexico in July 2019 to wait for their asylum cases to be decided in the U.S. After living at the migrant camp for nearly a year, they were among the first group to be processed for entry into the U.S.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

At a bus station in Brownsville, Texas, Guatemalan asylum seeker Jorge Mario Gonzalez shows scars from a surgery he had after being shot in his country. Gonzalez said he was shot near the ribs and the bullet went through his body, affecting a nerve, leaving him needing crutches to walk. He and his wife were sent back to Mexico in July 2019 to wait for their asylum cases to be decided in the U.S. After living at the migrant camp for nearly a year, they were among the first group to be processed for entry into the U.S.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Dinora Cruz, an asylum seeker from Honduras, explains why she left her country, in a bedroom in Matamoros, Mexico, that she shares with another woman returned under the Migrant Protection Protocols program.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Dinora Cruz, an asylum seeker from Honduras, explains why she left her country, in a bedroom in Matamoros, Mexico, that she shares with another woman returned under the Migrant Protection Protocols program.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Valery Sanchez, left, talks to her friend Natasha Mayorquin, both transgender women from Honduras, at Rainbow Bridge, a shelter in Matamoros, Mexico, for LGBTQ asylum seekers. Both moved to the shelter because they feared for their lives at the Matamoros migrant camp.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Valery Sanchez, left, talks to her friend Natasha Mayorquin, both transgender women from Honduras, at Rainbow Bridge, a shelter in Matamoros, Mexico, for LGBTQ asylum seekers. Both moved to the shelter because they feared for their lives at the Matamoros migrant camp.

(Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

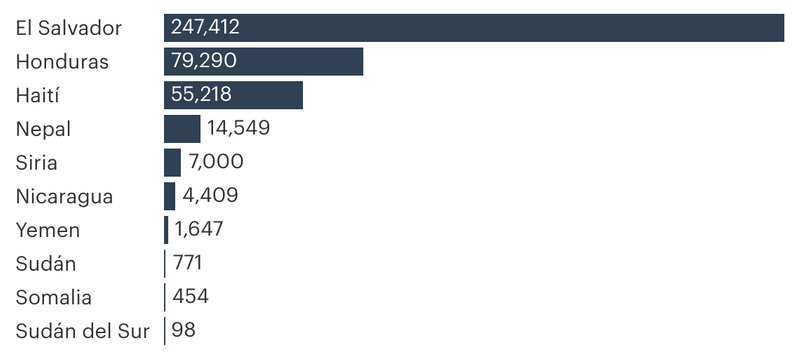

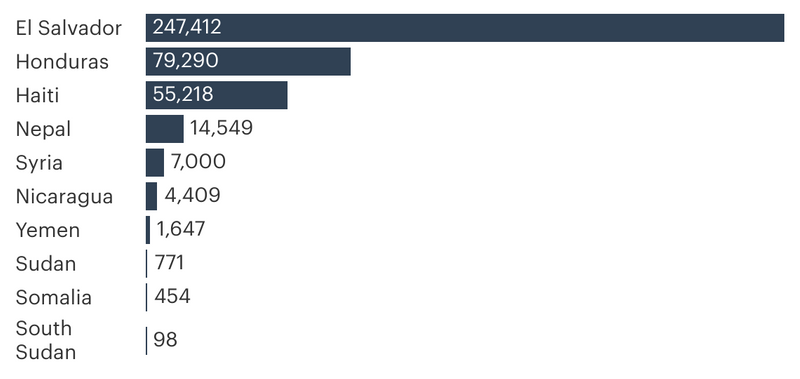

Fuente: Registro Federal y Servicio de Investigación del Congreso vía [Centro de Investigación Pew](https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/01/immigrants-with-temporary-protected-status-could-be-offered-a-path-to-u-s-citizenship/)

((Dara Lind/ProPublica))

Fuente: Registro Federal y Servicio de Investigación del Congreso vía [Centro de Investigación Pew](https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/01/immigrants-with-temporary-protected-status-could-be-offered-a-path-to-u-s-citizenship/)

((Dara Lind/ProPublica))

Source: Federal Register and Congressional Research Service via [Pew Research Center](https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/01/immigrants-with-temporary-protected-status-could-be-offered-a-path-to-u-s-citizenship/)

(Graphic: Dara Lind/ProPublica)

Source: Federal Register and Congressional Research Service via [Pew Research Center](https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/01/immigrants-with-temporary-protected-status-could-be-offered-a-path-to-u-s-citizenship/)

(Graphic: Dara Lind/ProPublica)

Circumstantial evidence suggests the crash could be a case of human smuggling turned deadly.

(Patrick T. Fallon/AFP/Getty Images)

Circumstantial evidence suggests the crash could be a case of human smuggling turned deadly.

(Patrick T. Fallon/AFP/Getty Images)

fière d’être aux côtés de

fière d’être aux côtés de